R.L Elson analyses the decisions, impacts, and outcomes of having cosmetic surgeries and procedures through the concepts of feminism, anarchy, and choice.

By R. L. Elson

Lip fillers, botox, liposuction, Brazilian butt lifts, face lifts, nip/tuck, nose jobs, breast lifts, breast implants, and buccal fat removal. These are just some of the more popular procedures available today that, 50 years ago, would have been considered rare and radical operations. These days, they are much more common and raise fewer eyebrows than going for a manicure. On online platforms such as Instagram and TikTok, many influencers are not only reliant on these procedures, but will often document their experience (typically luxurious) of 'getting work done'. Ranging from incredibly expensive all-inclusives at opulent resorts to more budget-friendly everyday procedures, it seems like everyone online and in the public eye is getting work done.

Cosmetic surgery used to have a negative connotation of being anti-feminist, or as being for a certain type of woman. Yet for many, having cosmetic surgery is essential for getting ahead in their careers. Indeed, there is such a strong normalisation of the constant inspection of our faces and bodies – especially in the age of social media – where when ‘fault' is found, it is corrected immediately, either by filter, makeup, or surgical means. This relationship of ‘fixing’ our bodies to ‘increase opportunities’ is a surreptitious way of commodifying ourselves into a visually consumable product. In other words, there is a relationship by which people modify their body in order to ‘add value’ to it, and thus get ahead in life.

However, a key Anarchist principle is that people are intrinsically valuable, regardless of their looks, bodies, or abilities; when this line of thinking is departed from, so begins a slippery slope towards ableism and eugenics.

But not all are anarchists. And, indeed, others would argue that having cosmetic surgery is a personal choice that allows for autonomy over themselves and triumph over brutal self-image issues. So, where do autonomy, feminism, and anarchy fit into this newer wild world of plastic surgery?

Background

Before embarking on a deep dive into cosmetic surgery, it is important to define what it is and what some of the common procedures are. A number of procedures exist that are technically not cosmetic surgeries; however, they utilise new body modification technology to shape and change the face (i.e. lip filler/augmentation).

Previously, hot debates would discuss the differentiation between medically necessary surgeries and elective cosmetic surgeries. But where does elective surgery end and medical surgery begin? These lines are incredibly blurry, and one wonders about the point of making the distinction.

Abdominal hernia repairs are great examples of how blurry these decisions can be. Hernias are when a loop of the intestine or fatty tissue pokes through the abdominal muscle wall. Hernias can be dangerous and painful, or they can be relatively painless and less dangerous/risky. In 2020 and 2021, over 15,800 abdominal hernia repairs were done as elective or ‘aesthetic’ surgeries. The decision as to whether a hernia repair, or any other procedure in the USA, is medically necessary or elective is made in a system where money decrees the bottom line. This decision is not always clear and people can live for years with hernias.

A survivor of an acid attack gets plastic surgery to help reduce the scarring on their face; this is considered to be elective and cosmetic. Gender-affirming surgeries, such as top surgery (i.e. to remove or augment the tissue in the chest), bottom surgery (i.e. metoidioplasty, phalloplasty ,vaginectomy, oophorectomy, etc.), or facial surgeries occupy another area of surgical care that is highly debated within the public sphere. However, it is only debated with such a fervor due to transphobia and homophobia. Studies have found that less than 1% of recipients regret having gender-affirming surgical care (for context, according to the most conservative estimate, around 7–8% of parents regret having children). Indeed, gender-affirming care is often an incredibly effective way for trans and gender nonconforming people to be protected from suicide and self-harm.

There is rarely the same fervor when a cis woman gets breast implants in comparison to a trans woman. Indeed, when cosmetic, elective, or aesthetic procedures are done, they are done not because of a threat to life; they are voluntary.The most common procedures done in the US are liposuction (fat removal), breast augmentation, abdominoplasty (tummy tuck), mastopexy (breast lift), blepharoplasty (eyelid surgery), and breast implant removal/replacements. Rhinoplasties (nose jobs), buccal fat removal, lip fillers, and Brazilian butt lifts are common as well.

Is there a difference between a trans woman getting breast implants or a cis woman getting liposuction? Or between a trans woman and a cis woman getting breast implants? What if the cis woman was getting breast implants after a double mastectomy? Are breast implants across the board considered to be gender-affirming care regardless of gender identity and/or sex? At what point can one judge the difference, and to what end? Where can the line be drawn, and who draws it?

Surgically altering one’s body is that person’s prerogative. It is, ultimately, a person’s choice, and some would argue, their agency to decide. Body modifications, such as ear-gauging or tongue-splitting, are similarly permanent and beg a question of autonomy.

But body modifications are seen differently in the public sphere in relation to plastic surgery. In the UK, the legal status of such procedures, like tongue-splitting or scarification, is extremely murky. In 2018, the Court of Appeals ruled that regardless of prior consent between the client and the practitioner (in this case, a registered tattooist/body piercer), tongue-splitting is bodily harm and illegal. This ruling followed the precedent of an older but infamous law, known as R v Brown (A) 1997 1A.C. 212, which proclaimed that consent between parties was not a justification for bodily harm. As the Court said,

The satisfaction of sado-masochistic desires does not constitute good reason for the infliction of bodily harm or wound.

In other words, this ruling made BDSM illegal, and though an appeal was launched under the European Court of Human Rights (Article 8’s right to privacy/home life), it lost1. To what end is the State allowed to dictate choice over people’s bodies, especially between two consenting adults?

In the US, of course, that question opens a large can of worms, especially in regards to women’s bodies. The procedure of ending a pregnancy has been under attack for decades, with a recent increase in vitriol and violence; this issue of autonomy has been at the center of feminist struggles for centuries. Anarchy as praxis would dictate that it is absolutely not the business of the State what someone does with their body, and that it is the duty of everyone to ensure that bodily autonomy is prioritised. Indeed, feminist anarchism fights for the right to abortion, but does it fight for plastic surgery?

Traditional strands of feminism would say that plastic surgery contributes to a culture of misogyny, reinforces sexist ideas of what is a ‘beautiful’2 woman, and caters solely to appeasing the male gaze. However, many people who have had cosmetic procedures or are saving up for them would say that it is solely for themselves. So, how can the ideas of agency, autonomy, and anarcho-feminism be used to deal with the messy contradictions of everyday life under white supremacist patriarchal capitalism?

Plastic surgery and capitalism

Labour is what underpins capitalism. For many, their image is their capital. From actors to influencers to sex workers3, having work done is very common and frequently expected. Of course, not everyone in the previously mentioned industries have had procedures done, but many have4. The more money one has, the more they can afford to pay for procedures that look subtle or ‘natural’ by certified and boarded surgeons. For those who are not in that tax bracket, they may risk their health by having ‘back alley’ procedures by non-licensed surgeons. As it goes, there is a trend in the UK of people flying abroad for cheaper procedures, with deadly consequences5.

Indeed, many actors are hounded by the press surrounding their alleged surgeries, while other celebrities may end up on programs, articles, tabloids, or posts as exemplary of the Worst Celebrity Surgeries Gone WRONG. TV shows such as ‘Botched’ further the spectacle of perverse fascination and revulsion at those whose body procedures had a bad outcome. The plastic surgery industry has proliferated across the media, demonstrating how normalised it is, but the stigma has evolved and endures. Yet for those in the limelight, the pressure to look a certain way is tantamount and can be critical to landing roles in films and TV, or landing clients.

For sex workers6, having a certain type of body is crucial for making money. While there is a niche and audience for everything, there is typically a certain look that tends to be popular. Usually, this consists of long fingernails, big eyelashes, a small nose, big lips, tan but not dark, larger breasts but still perky, thin with long legs, and a plump posterior. For influencers, their look is their brand, and that brand is incredibly lucrative. There are countless stories of how an influencer posts a bad photo and then loses followers, thus losing revenue.

While makeup contouring and lymphatic massages can do the trick for a night or a single post, many in these industries will also get surgery. The payouts from these overlapping industries are potentially huge and are accompanied by the possibility of making lots of cash, fast. For those who are able to access this market, it can mean financial freedom, success, and a level of independence and autonomy rarely accessible under capitalism.

The point here is that people will often have to ‘invest’ in their bodies in order to get business. Plastic surgery is a huge business in and of itself, with Americans spending $14.6 billion on aesthetic procedures in 2021 and around $11.8 billion in 2022. The data7 is fascinating, as in 2021 the total surgical revenue increased around 63% from 2020. Women accounted for roughly 94% of all procedures in 2021, and 95% of all procedures in 2022 (The Aesthetic Society, 2021;2022). The boom in aesthetic surgeries in 2021 was not limited to the US, and probably comes from elective surgical clinics re-opening post lock-down and because of the ‘Zoom Effect’ (the hyper-awareness of ones' appearance).

On an individual level, it is critical that people are given the right to do what they wish with their own bodies. Yet on the collective level, it is hard to ignore the way that these individual choices are pressured by capitalism and status, and further skew toward trends of White misogyny.

White supremacist patriarchy and plastic surgery

The decision to get a cosmetic procedure is not a simple fiscal calculation. It is extremely personal. An individual may have grown up struggling with intense dislike for one part of themselves, and finally feel affirmed, excited, and thrilled with their new body part[s].

But a question to ponder is this: where did this dislike come from? It cannot be a coincidence that the top aesthetic procedures done are liposuction, breast augmentation, abdominoplasty (tummy tuck), mastopexy (breast lift), blepharoplasty (eyelid), and breast implant removal/replacements. All the surgeries tend towards making someone skinnier, with perkier and larger tits and Western features.

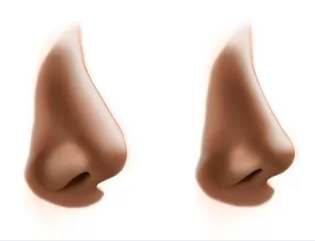

There is a significant racial aspect to the trends of different plastic surgeries that cannot be ignored. The double-fold eyelid surgery (formerly called Asian blepharoplasty) is one of the most common procedures in Asia and amongst Asian Americans. This surgery transforms an eye without a hooded lid to one with, as seen in the photo below:

The second photo is the ‘after’ photo, where the desired effect is to have a hooded lid, a feature less common in Asia.

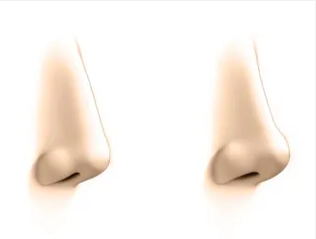

Rhinoplasties, commonly referred to as ‘nose jobs’, are not divorced from eurocentric standards of beauty (except in certain cases, such as in the reconstruction post accident – fire, acid, car wreck, etc. –, widening the nose to help one breathe, cleft palate, and other similar situations).

In a quick search for rhinoplasties, one of the top results helpfully explained the different types of rhinoplastic procedures for different ethnic groups. Here are the photos:

From left to right: Middle Eastern; African American; and Native American.

These photos were found on an advertisement page, with links to become a new patient and with an article titled The art of ethnic rhinoplasty: a nose job that preserves your cultural identity.

While it is a positive that the article is advocating for procedures that give medical treatment to different ethnicities, it is not the only racialised aspect of cosmetic surgery. This is reminiscent of the trend of skin bleaching, where darker-skinned people would quite literally bleach their skin in order to become lighter. This practice is still huge and is a global multi-billion pound industry. It’s estimated that in 2018, that 61% of women in India, 77% of women in Nigeria, and 40% of women in China regularly used skin lightening products. Systemic discrimination is still alive and well. People who have lighter skin are routinely favored in almost all aspects of societal life. This concept is known as colourism, and more information can be found here, here and here.

Young people, especially those raised as women, are bombarded with messages that they are not enough. Whether this is through ads, ‘glow-ups’, ‘make-overs’, or romance films where the heroine changes herself to be found desirable, the outgoing message is this:

In order for someone to love you or find you desirable, you must change yourself into someone who is conventionally attractive (read: skinny, young, light-skinned, traditionally feminine, etc.).

This is furthered through social media, where status and wealth are prized alongside beauty types and body ideals. What is more, is that it is accessible, commodified, and sold to the tune of, ‘if you want to get ahead, be beautiful and successful, here is how you do it...anyone can do it’.

This type of messaging is particularly compounded for women, who are constantly told that they must stay young and beautiful. It is a double-pronged spear that marginalises older women and hyper-sexualises children. When women are found to no longer be ‘desirable’, ageism partners with sexism to render older women ‘invisible’.

The cosmetic surgeries that are popular tend to be those that encourage features commonly associated with youth. Botox and facelifts specialise in making wrinkles disappear, firming and toning skin to give a youthful appearance. This trend towards smooth skin assuages people’s fear of aging; however, it often can tie into the hyper-sexualisation of children.

The smooth, wrinkle free skin usually goes in tandem with hairless features. For women, hair removal has been considered fashionable since the 1960s, and the methods of hair removal are constantly evolving: shaving led to waxing, to epilation, to threading, and most recently, to laser hair removal. The implications of finding women (and, increasingly, men) desirable who have no hair and smooth skin unconsciously, or indeed, extremely consciously, signal that the characteristics of a child are sexy. When the phrase ‘hyper-sexualisation of children’ is used, this is one meaning.

Another characteristic of the ways in which western society hyper-sexualises children is through the infantisation of women. Memes such as ‘I’m baby’ or ‘I’m just a girl' play into a dynamic of someone who is incapable, needs help, and can not be expected to know or understand something because they are a girl.

This dynamic is then reflected to the male counterpart who is supposed to be ‘protective’ in a way that is sexy, and yet very reminiscent of parental guidance. The point here is that it is more and more seen as desirable, and indeed can be lucrative, for a woman to look young and act childish whilst being sexualised.

The false dichotomy: Autonomy, Anarchism, and Feminism in regards to cosmetic procedures

Often in conversations about aesthetic procedures, a false dichotomy is raised: either you condemn all procedures because they skew towards racism and misogyny, or you encourage people to do what they want because they must have bodily autonomy.

It is important to consider a third option. This option is much more uncomfortable, because it is not black and white and requires holding overlapping truths. It is both and all; agency and autonomy over one's body are of the utmost importance; yet, all of our choices and decisions do not happen in a vacuum. How much agency can one truly hold if the path of elective procedures opens doors to a life of less discrimination and more potential financial gains? How can one measure the insidious coercion of white supremacist capitalism against the wants and desires of an individual? While celebrating people’s choices to empower themselves, it is worth examining where these desires come from.

In other words, on the individual level, people must have bodily autonomy and agency, which does include splitting tongues, having abortions, piercing genitalia, gender-affirming surgery, and yes, cosmetic procedures.

Someone may have grown up struggling with intense dislike for one part of themselves, and finally feel affirmed, excited and thrilled with their new body part[s]. And it is important to support and celebrate when someone takes control over their body and makes it their own!

Simultaneously, it is important to hold the collective alongside the individual. There is a message that gets sent, albeit sometimes unconscious and unintentional; it reverberates out and contributes to unrealistic beauty standards that are set by white patriarchy and capitalism, and are reinforced by social media influencers and advertisements. In other words, our society creates the conditions for people to grow up in a state of intense struggle with their bodies, and while surgeries may provide relief for individuals, their stories contribute to the dominant myths around beauty. This beauty myth compounds social pressure, and underpins the harm in society that radical work of self love is trying to undo.

It is also important to consider why someone feels compelled towards popular cosmetic procedures such as breast implants, liposuctions, or a rhinoplasty.

It is rarely only a fiscal decision, but rather a deeply personal and emotional choice. But what exactly is so horrible about having small tits or a large nose? Why is it that this type of affirmed care by the aesthetic beauty industry typically leads to one specific look, which is that of a western, slim, perky, but large-breasted woman?

Perhaps it’s too easy to respond by saying that it is due to internalized colonial misogyny with a walloping heaping of targeted advertising to break down self-esteem and tempt people into status and wealth through altering their bodies. The increasingly common practices of shaving, lip-filling, and use of tanning beds add to a culture in which all members of society are expected to ‘work’ on their appearance. These practices reverberate beyond the individual and apply pressure on the collective to achieve these body standards.

There is a trend of ‘feminism’ where acts of feminine expectations are marketed as ‘radical’. It is another way that capitalism has co-opted and commodified the once radical and feminist articulation of self-love. The evolution of this narrative within feminism has sharply turned since the 1980s. Now, modern trends reject the notion of framed victimization by beauty standards, and instead claim empowerment through these expectations. For example, it is common to see slogans such as 'make your winged eyeliner sharp enough to kill a man!', examples of which are provided below:

This framework of empowerment lacks evidence, furthers profits for the beauty industry, and extends the same expectation that women must be a certain type of beautiful. Again, this is a question of individual versus collective; for the individual, framing expectations as empowerment may provide relief against the rigid societal structure, but for the collective society, it coalesces in simply another woman who falls in line with societal expectations.

This line of thinking extends to those who buy in to the aesthetic beauty industry. It is fine to get cosmetic surgery and still fight the patriarchy, but one act does not equal the other. In other words, getting breast augmentation is not a radical feminist act, and that is okay. It is also more than okay for people to get the treatments that they want, but it is foolish to act as though this is a grand example of feminist praxis. It should not be restricted by any means, and people should not feel shame for how they chose to inhabit their own body. However, it is a disservice to call this kind of cosmetic surgery a ‘radical act’. Radically affirming oneself would go much deeper than the aesthetic beauty industry, and beyond the individual. It would consist of a deep uprooting of toxic beauty standards. As Crimethinc once wrote:

Beauty must be defined as what we are or else the concept itself is our enemy.

1 This law probably came to be under homophobic intentions.

2 'Beautiful' is in quotes, because it is extremely subjective.

3 Note: these categories are not distinct and tend to overlap.

4 Think of your favorite actor or actress: the odds are that they will have had some kind of work done.

5 Unfortunately, there is not enough space to go into the subject of Medical Tourism.

6 This term encapsulates a wide range of professions, both online (cam-models, onlyFans, phone operators) and in-person (sugarbabies, strippers, escorts etc.).

7 This data is from the Aesthetic Society and Ronan Solutions, and comes from 294 plastic surgery practices in the US. This data is from surgery reported and performed by board-certified surgeons.

Comments ()