Patrick Derieg considers the future of AI. Will we allow big tech companies to solely own Al, or will we take collective ownership over these increasingly powerful technological tools?

by Patrick Derieg (translated from German by Christopher Hütmannsberger)

For a year now, the EU parliament has been collecting suggestions concerning the regulation of artificial intelligence (EU AI Act). On 14 June 2023, the first negotiation positions were agreed upon. These positions essentially establish norms that regulate both the general development of the field of AI and that of certain applications specifically within it. The aim is to ensure compliance with these norms.

The first part of the Act involves an attempt to counteract risks and misuse. On the surface, this is described as the use of AI for political campaigns, spreading disinformation in social media, facial recognition, deep fakes, and other acute dangers. Also mentioned are the long-term dangers that could be posed by general-purpose AI models that far surpass the abilities of currently available models (the theoretical danger of an artificial super-intelligence, or the so-called AGI, Artificial General Intelligence).

The suggested mechanism to ensure compliance with these norms would not only impact commercial providers, but also open-source projects. Making tools available that have not been inspected would be subject to high fines. This means that simply the development of powerful tools in itself, and not just their (malicious) application, would be classed as a crime.

In general, it is a good thing that new potential dangers are recognised and discussed on a parliamentary level. Even if you are not convinced that the development of an artificial super-intelligence is on the horizon, there are more than enough reasons to look for answers to counter the already existing dangers emerging within the field of AI (ChatGTP-inspections as pretense to ban books in the USA, Revenge Porn, Fake Kidnappings, …).

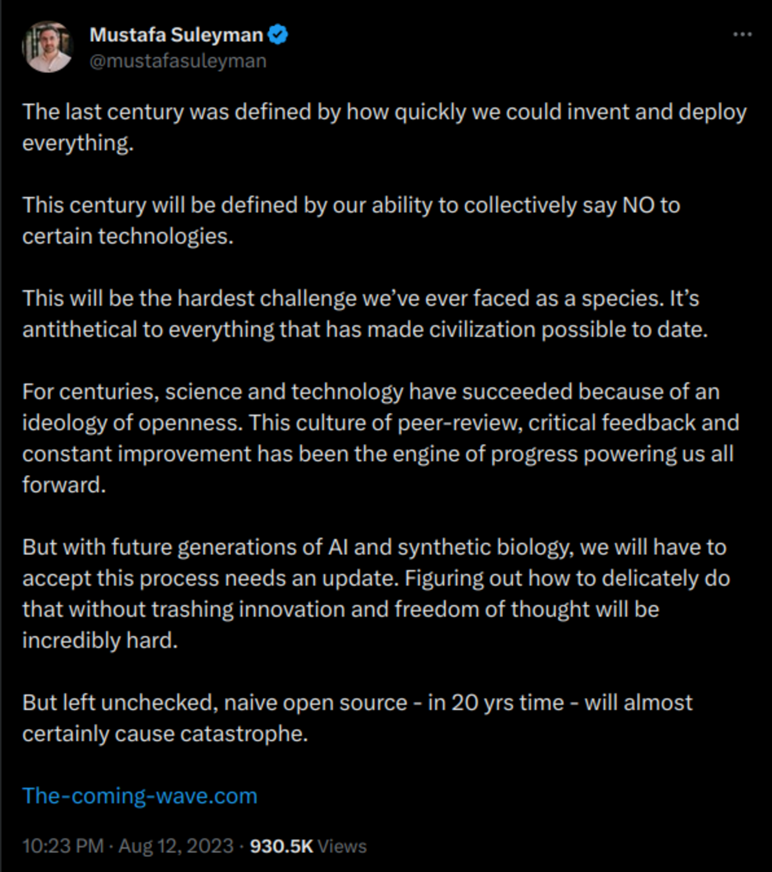

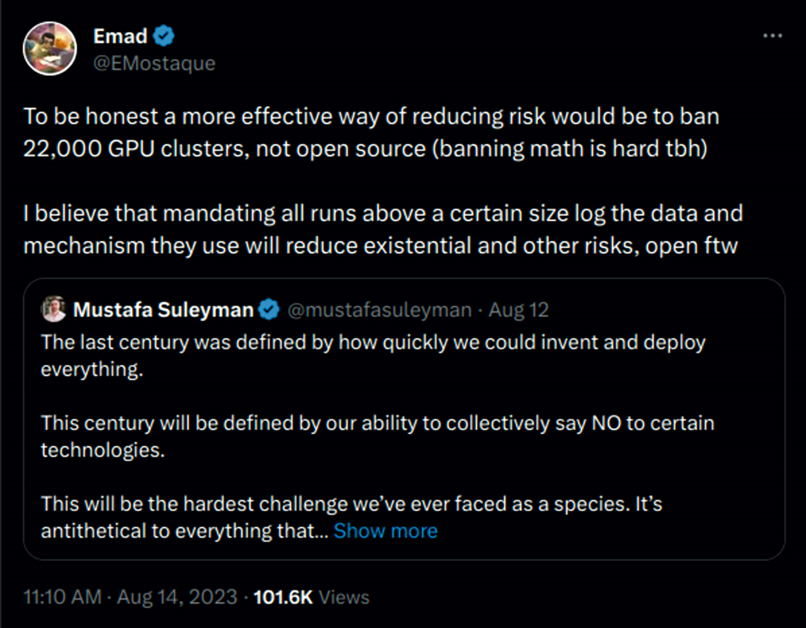

Another legislative suggestion comes from the tech giants themselves, such as Google. They propose something called FAR (Frontier AI Regulation). Here, they argue that access to these powerful technologies should be restricted entirely to the big players, and that governments must quickly implement laws in order to avoid an apocalyptic scenario.

Proponents of this plan have been lobbying since the beginning of the year, and also seem to have left their mark on the EU AI Act. They insist on the existential threat of the technology itself. On the other hand, critics of FAR see the increase and cementing of these power dynamics as the existential threat.

We currently find ourselves at a decisive crossroads. Either a centralised elite will shape the development of these powerful tools, or this power will remain accessible to all. These two scenarios (concentration of power vs. distribution of power) are mutually incompatible. If we take the speed of current developments under consideration it appears likely that, regardless of the path that we choose, there will be no turning back.

Scenario A: AI belongs solely to tech companies.

The argument is that only a centralised AI can ensure that we can direct a course of action and thereby avert misuse. If we were to accept this (which we should not, but assuming we do), then we can think about what this would mean within legislative practices.

In order to create powerful AIs you need graphic cards. These are the same that you need to play video games. In order to create large models – comparable to ChatGPT – you need a lot of them (as well as water and energy). Apart from large tech companies and national governments, these are resources that very few people have access to. Therefore, competition or alternative models can hardly be developed.

Any data-centres that open up in spite of this restriction and produce similar models would represent an existential threat and must be (quickly) destroyed before they are in a position to challenge the powers that be.

However, the computational power needed to create such new models does not have to be concentrated in a single centre. As proven by organisations such as BLOOM and TogetherComputer, the public as a whole could volunteer their home computers in order to contribute to the creation of such models. Doing something like this hardly requires any technical know-how and could very easily become even more accessible in the near future. Preventing such a collaborative endeavour would require the surveillance of every private computer, as well as many, many criminal charges.

Additionally, it is important to mention that such wide reaching surveillance would be rendered utterly useless if it stops at a nation’s borders. This means that its implementation would require treaties between every country on the planet. Any country that does not abide by these strict surveillance regulations again represents an existential threat. In the words of Eliezer Yudkowski (a prominent expert in the field of AI), this leaves only one answer: nuclear annihilation.

But if all of this is implemented, we are safe, right?

This solution, that might seem perfectly viable on the surface, has a small catch. In contrast to a nuclear bomb, which is something that is hard to come by, even the mightiest AI model consists of zeros and ones that can be transferred easily via flash drive or an internet connection. Even if we assume that our tech overlords truly only want what is best for us and that they will use their AI models exclusively for the good of all people, it only takes a single bad actor with access to their models to turn the world’s power structures on their head.

Possibly – this is the hope – mechanisms can be developed that will allow for a powerful AI model to be shut down from a distance. These will carry such a degree of certainty that we will be able to safely wager the future of humanity on it. This is something that is currently still in development.

But THEN we would have it. Yes... Then we would all be safe.

Scenario B: AI belongs to us all.

If AI technologies are made available to everyone, then there will invariably be many people who use the technology maliciously. AutoGTP is an open-source project that allows users without any programming experience to create autonomous agents that follow a certain goal. As this system, and the language model on which it is based (Chat-GPT) is still limited in certain aspects, these agents – depending on the complexity of the task – will get stuck. But it is worth mentioning (even though it is not surprising) that there are already innumerable such agents with the goal of ‘destroying humanity/civilisation/sowing chaos’.

Many cyber security experts have been more vocal as of late: the principle of ‘many eyes make all bugs shallow’ – a programming expression that refers to the fact that, through collaboration and collective oversight, solutions can be found for even the most complex of problems – is also something that can be applied to the field of AI. Open-source technologies are the backbone of the internet itself. They also support countless software products and services that have proven to be secure due to the contributions and troubleshooting conducted by a world wide open source community; indeed, they are much more secure than if there were left solely in the hands of small teams developing proprietary solutions.

To put it differently: who can react faster to potential misuse? Every cyber security expert in the world, or a handful of companies? Browsing through the many examples of AI-generated books on Amazon or searching for the term ‘as an AI model’ on Google Scholar, you will quickly come to the conclusion that such companies are in no way prepared to react to cases of misuse (assuming they consider themselves to be responsible for moderating this in the first place).

Let us assume that we choose the path of making AI technologies available to everyone. What else will happen?

New statistics show that in an increasing number of areas (image recognition, understanding text, programming, and more) the abilities of AI models are already surpassing those of human beings. A project by Harvard Open-Source recently made waves. In this project, figures controlled by an AI language model populate a virtual world. Running a simulated world on local servers in which AI agents carry out their own jobs (with real world results) is no longer in the distant future: imagine a world in which we as a society could profit from this, rather than being replaced by similar systems.

All content could be brought to us personally. Endless new connections based on a humanly insurmountable number of sources could be made. The creation of software, or companies, or operas could be achieved by formulating a paragraph. Solutions for real crises could be explored and found. This gigantic collaborative project that we call the internet could manifest itself anew through AI, for the betterment and empowerment of society as a whole.

However, this is also where the problem lies: we know that the participation and empowerment of society as a whole has to be prevented by any means necessary.

Concerning these newly drafted proposals I want to remind you of something: the DPA (Data Protection Act) is the law that ensures that we are asked within Europe whether or not we want to allow a website to use our data. This law is from 2018, over ten years after the theft of our data had become a billion-dollar industry. The political landscape proves time and time again that our (even prior to the internet) dust-covered structures can absolutely not keep up with the rapid development of the internet. AI will move significantly faster.

It is important to note that the DPA was implemented in order to counter the unregulated accumulation of capital. If our representatives give in to the pressures of the tech giants, then they could easily attempt to create a form of centralisation. The first laws that pass in this regard could already seal our fates.

It is my call to everyone, no matter your background: inform yourselves, inform others, take part in this discussion. This matter has the potential to either open up possibilities never seen before, or plunge us into the deep. Let’s not let Silicon Valley decide.

Patrick Derieg is a freelance IT technician from Linz, Austria, who deals with the history of IT and free software.

Originally published in German in Versorgerin #139, 1 September 2023.

Comments ()