With the world in dire straits, R. L. Elson argues that hope as a practice is critical. It must be cultivated and it forms an unavoidable first stage of action.

by R. L. Elson

The world is in dire straits. The current genocide unfolding in Palestine where families are being decimated, the land is being subjected to ecocide, and the few survivors are at extreme risk of starvation, infection, and disease (that is, if they aren’t murdered by the IDF, as their newest campaign is targeting Rafah’s1 refugee camps) comes to mind. The environmental impacts of this onslaught are still unknown, yet can be assumed to be devastating, on top of the human pain and suffering being caused. The flames of anti-Semitism, xenophobia, and Islamophobia are being fanned, while in Sudan, Congo, and many other places people are fighting for their liberation. In the West, the profiteers of neo-colonial endeavors are making scads of money while workers in the West are faced with increasing precarity, a cost of living crisis, mounting prison populations and diminishing social services.

In other words, it would be easy to say that everything is fucked.

However, I am here to argue that it is imperative to our future that we practice the radical belief of hope.

Why is hope radical and what makes it a practice?

Legendary abolitionist theorist, writer and activist, Mariame Kaba, said,

Hope is a discipline […] It’s less about ‘how you feel,’ and more about the practice of making a decision every day, that you’re still gonna put one foot in front of the other, that you’re still going to get up in the morning. And you’re still going to struggle, […] It’s work to be hopeful.

The phrase that hope is a discipline has garnered a lot of attention, both positive and negative. One article, by Decoloniza, strongly disagrees with Kaba, saying that 'hope [….] significantly relies on power, privilege, and/or capacity. In the face of constant systemic abuse and a lack of truly transformative accountability; many lack faith in antiblack, capitalist, and/or settler institutions and their “chosen” leaders. Therefore, many lack the power, privilege, and/or capacity to hope. They become incapable of hope. The ability to imagine beyond the carceral status quo requires faith not just in one’s liberatory imaginings but faith that the imagined can be confidently materialized… hope as a discipline requires us to lower our expectations of liberation'.

As someone with different intersections who has been organizing for years, I have not found this theoretical application to be true. Firstly, this reasoning is circular. If those who are oppressed cannot hope, and thus don’t have a reason to organize for better conditions, either gains won’t be won, or a savior must arise from outside the margins (which is problematic in its own right). Secondly, to limit hope as being reserved solely to those with power and privilege is removing a lot of agency and autonomy to those at the margins. Lastly, having hope, in general, is not the same as having hope in violent institutions which have continuously proved time and time again that they serve everyone except for the people.

When I say I have hope, I mean I have hope in my comrades; in the people I see putting their lives on the line to fight for change every day. I certainly do not mean that I have hope in the legal system to bring about justice to those who have been deeply harmed. Indeed, hope is not faith; it is the belief in the possibility of change.

Hope, alongside imagination, is critical for fighting for a better, different, liberatory tomorrow. Steve Biko said that the most potent weapon of the oppressor is the mind of the oppressed. So how can the chains of the mind be cast off?

There are many different, ever emerging ways to unlearn the dominant teachings that lie dormant in your head. It is valuable to look to the past, as older generations have hard fought for insights that shed light upon our current struggles.

A slogan that has been carried through to today calls for you to “kill the cop in your head.” More recently popularized in the late 1990s by Lorenzo Ervin, who used it to call for the end of white anarchists policing the actions of fellow black anarchists within the movement, this slogan dates back much earlier to the late 1950s. A group of anarchists, students, leftists, workers and artists formed the Situationist International in 1958 and proved to be critical to the May 1968 Parisian uprisings. The earliest recording of this slogan was found graffiti’d in Paris, saying:

Un flic dort en chacun de nous, il faut le tuer

(A cop sleeps inside each of us, it must be killed);

Chassez le flic de votre tête

(Drive the cop out of your head).

This concept found its way to Augusto Baol in the late 1970s, who, taking influence from Paulo Friere, wrote Theatre of the Oppressed with this concept in mind. Simply put, the cop in your head metaphor means that your oppression is internalized, and within you there is a figure preaching its oppressive values.

For example, the police demand that we follow the law without question. However, there are laws which morally command us to break them. Yet, there will be people who, due to the policeman in their head, will continue to enact their own oppression and the oppression of others.

Another way of freeing the mind comes from mobilizing the imagination. There is a long line of radical science fiction authors who push the bounds of imagining what a new world might be. Marge Piercy’s time-travelling seminal piece explores a world without gender, possessions, or capital. Ursula le Guin has been widely lauded for her work, notably The Dispossessed and The Left Hand of Darkness. Octavia Butler is hailed as a visionary in science fiction, with mass followings (see adrienne maree brown’s podcast), and a field of studies dedicated to her work.

Indeed, Octavia Butler reminds us that the “only lasting truth is change”. Everything is changing, which means that there is a possibility for a better outcome at every junction. So why not imagine that at the next shift, the next junction, things may move towards the better?

Those who are active in community organizing, those who study movement ecology, and many others have spent a considerable amount of time trying to figure what exactly makes a historic moment emerge. What led to the previous mentioned Parisian uprisings of 1968, and why was it that at that specific time that the industrial workers joined in with the students as opposed to other times?

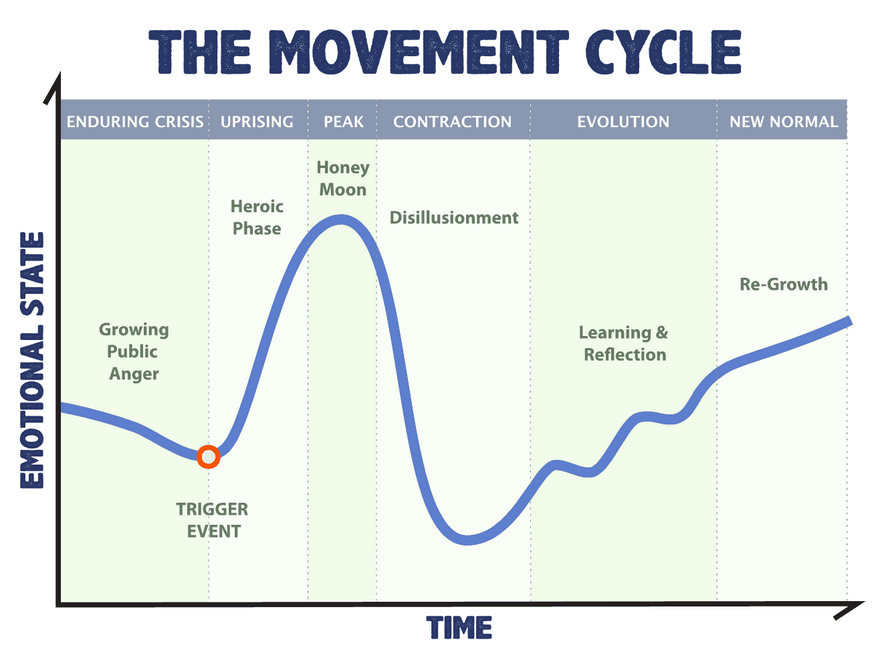

Some models of social movements will point towards a cycle, seen here:

However, this movement cycle is not convincing to all, nor is it wholly conclusive. Moreover, it is ever continuing and cyclical, meaning that uprisings can occur at any point.

Mariame Kaba and other elders within social movements speak about la longue durée; that the fight for liberation is a continuous process, a marathon which requires stretching and hydration, rather than a sprint. This longer process asks for a longer gaze, one that looks back at the past to inform us, and forward to the future with determination and hope. We don’t know where the next waves of radicalization are going to land, indeed, sometimes we don’t even realize we were in the wave (so to speak) until we reflect and look back. Therefore, why not practice having hope that the wave will hit sooner and bigger than before?

Without hope, it is easy and even tempting to slip into despair. Why bother showing up to the protest if it’s not going to change anything? Why bother organizing for medical aid if the bombs are going to keep falling?

This is exactly what fuels the dominant paradigms: when you are demoralized, demotivated and devastated, the likelihood of you organizing to resist is lower.

Hope is a practice. Having hope, like doing the crossword, is a muscle that gets stronger the more you do it. I want to clarify that does not mean holding a blind belief in an instantly better tomorrow, nor is it an allowance to do nothing because you hope that someone else is going to take care of it for you. This practice is a belief in the possibility of a better tomorrow.

While it is critical to continue, it is more difficult to do. Therefore, it is useful to try and practice having hope, even when the feelings are not actually there. Below is an exercise that has been used at previous movement building trainings/conferences:

Take five minutes to close your eyes and imagine the world post revolution. What does that look like for you in your everyday life? Try to imagine a day in the life where there is no racism, capitalism, patriarchy, colonialism, etc. Can you do it? Even briefly? When you wake up in that world, who do you see? What do you do? How do you feel during and after imagining this new life for a few minutes?

In a profound twist of irony, while I was trying to write this article I fell into a strong bout of depression, one of which I hadn’t experienced for some time. The devastation I felt was not purely due to brain chemistry. Watching your tax money contribute to a live screening of genocide, where everyday reveals a new and horrifying method of seeing how people are made to perish in cruel and unusual ways, is obscene. The psychological impact (alongside the fires, droughts, famine, ice storms etc.) of climate chaos on young people is still being studied; rest assured, the baseline knowledge that capitalists are too greedy to stop pillaging and plundering the Earth even though mutual destruction is guaranteed is enough to drive anyone into a crisis. I know that I am not alone in feeling this way; whenever I speak to my friends, family, and community when they are struggling with their mental health, a typical reason they will give is: “well, and what with everything that’s happening in the world...”

However, I am comforted by the fact that there is hope. There are people resisting, struggling together in solidarity, and making things less shitty.

Millions across the world have mobilized in support of Palestine: Conferences are being interrupted, businesses are being targeted (Palestine Action, Jewish Voice for Peace, Palestine Solidarity Campaign, and many many others). Stop Cop City is actively and continually defying the militarization of police and destruction of the Weelaunee Forest.

These collective actions of many different fractals create change. When we remember that we are not alone, when we remember that the system functions on our demoralization (and thus wants us to be demoralized) it is easier to resist the stickiness of despair.

Hope is critical. To have hope in the face of all the atrocities occurring is like spitting in the face of fate. Nothing is predetermined. Anything is possible. We are autonomous, powerful, and everywhere. We will win.

1Rafah is in the southern part of Gaza, on the border of Egypt and Palestine. It constitutes a critical location for entry for aid trucks/conveys. It is also where Israel deemed a “safe zone” for civilians turned refugees to seek safety; as of the time of writing this article, it is currently being bombed, raided, and at severe risk of famine due to prevention of humanitarian aid.

R. L. Elson is an organiser, activist and aspiring PhD candidate.

Comments ()