The history of International Business Machines (IBM), how they were used by the Nazis, and how one statistician gamed the system to save thousands of Jewish lives.

by Patrick Derieg (translated from German by Christopher Hütmannsberger)

Content warning: discussions of genocide

A video on René Carmille by Patrick Derieg.

The first census in the USA was carried out by hand in the year 1880. Equipped with paper, pen, and a catalogue of questions, thousands of agents travelled across this new country in order to try and determine how many people lived there, their gender, amount of children, and professions.

The census was conducted every ten years; however, the processing of the collected data itself also took ten years to complete. This was a long time, especially for a country that was going through such large transformations and had just experienced a civil war. The relevance of the collected data, intended to inform legislative decisions, was therefore rapidly becoming outdated.

Innovation and Acceleration

Herman Hollerith, an electrical engineer with German roots who was working in the US Census Bureau during this initial census, had an idea. He developed a machine that could retain data on punch cards, changing the entire process in one fell swoop. Rather than taking ten years, the census could now be completed in a few months.

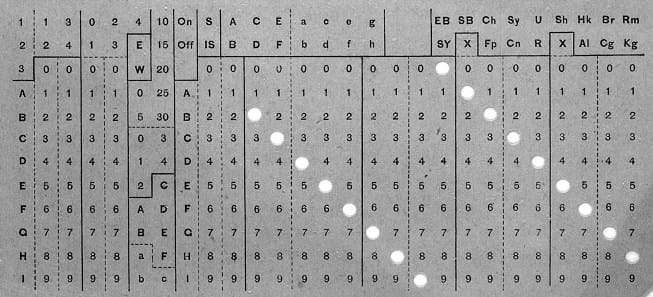

The system worked as follows: cards with charts printed on them were punched in such a way as to encode specific attributes or quantities concerning participants in the census. The cards themselves had a very specific chemical composition in order to conduct as little electricity as possible. As the cards were fed through a machine, they moved through electrical circuits, and it was only through the holes that the circuit was completed. In this way they could be sorted as needed, and thus could be processed much quicker than through the previous method, in which the exact same data had to be written down by hand and processed manually. This system created an analogue form of a database.

The system was a big hit, and governments all over the world wanted to get their hands on Hollerith’s machines. Herman was able to accumulate a small fortune thanks to the enormous demand. Not particularly business savvy, he did not feel comfortable in his new role as a CEO, writing as much in letters to his wife from lonely hotel rooms. It was not until the cunning businessman Thomas Watson took over the business with the backing of Charles Flint, a shipping and rubber magnate, and renamed Hollerith's company “International Business Machines” (IBM) after a merger, that the technology quickly became a worldwide success that had next to no competitors.

Hitler’s Census

European countries and large companies bought the system in order to take advantage of the huge increase in efficiency and the lower costs that this technology heralded. IBM branches were set up in several countries. In Vienna, Willy Heidinger, an acquaintance of Hollerith, set up a company entitled Dehomag (Deutsche Hollerith Maschinen Gesellschaft), a licensed distributor of Hollerith's machines, cornering the German market and giving the company a virtual monopoly. Heidinger was an ardent National Socialist. IBM would go on to own a 90% share of Dehomag in a hostile takeover, after Dehomag ran into trouble.

When Hitler came to power in 1933, his new government carried out their first census with the IBM punch card system. It included a question concerning religious affiliation. However, as Hitler felt that the initial census did not show as many Jewish people as expected, in the years leading up to the Second World War another three censuses were carried out with a revised question: religious affiliation now became linked to one's grandparents. Punch cards were also used in German industry (steel, arms, chemical production) as well as infrastructure (particularly the railway system). During this period, the German train system became famous for its punctuality.

In a speech by Heidinger, he compared the Hollerith machines to medical apparatuses; Hitler was the doctor, with a system that allowed him to take a more detailed look at the condition of his patient: the German nation. When the speech was sent to Thomas Watson in New York, he congratulated Heidinger for it.

Thomas Watson publicly took a stance against the sanctions that the international community issued against Germany. When elected as President of the International Chamber of Commerce in 1937, Watson held its congress in Berlin, where Goebbels organized a grand celebration in his honour and Hitler personally presented him with the Verdienstorden vom Deutschen Adler, the highest accolade that could be bestowed on non-German citizens. As a slogan for the congress, Watson chose “Weltfrieden durch Welthandel”: World Peace Through World Trade.

War

As Watson’s systems were already in use in multiple European countries, the Nazis were able to seamlessly continue their use of the punch cards after invading Poland, Holland and then France. In Hungary and Romania they also set up punch card offices where they carried out censuses according to Hitler’s criteria. The central punch card office in Berlin was situated directly next to the Reichstag and every day trucks filled to the brim with punch cards passed in and out of the building.

Hollerith had realised very early on that the real business was not in renting out the machines, but rather in the sale of the punch cards themselves. He chose the format of a one-dollar bill. If the format or the chemical composition was not exactly correct, the intricate and expensive machines ran the danger of breaking. In order to prevent any outside innovation, contracts of exclusivity in terms of the delivery of the punch cards were secured. In this way, Hollerith and later IBM could practically print their own money. The war only increased demand.

In order to highlight the role that the punch card systems had in the execution of the Holocaust, it's helpful to take a closer look at two distinct situations in Holland and in France.

In Holland, Jacob Lentz, a statistician who regarded himself as entirely apolitical and had a particular fondness for accuracy, was tasked with executing the census. Lentz completed his task with aplomb, in doing so delivering around 80% of Holland’s Jewish population to the Nazis. In France, this task was carried out by a high-ranking French military officer named René Carmille.

The First Ethical Hacker

In contrast to Lentz, Carmille was able to delay the results for multiple years. Not a single punch card that came out of his office was ever punched in a way that would identify a person as Jewish.

During this time he also developed an encoding system that assigned a number to each French citizen that included specific attributes (gender, military status, profession). With this system he was able to identify hundreds of potential resistance fighters and organize them into an army in exile. This encoding system went on to become the basis of the French social security system. Carmille would risk his life again, travelling to Geneva with no official reason in order to communicate his insights to an IBM representative in the hopes that Thomas Watson would be notified of the insidious ways that his technology was being employed.

René's activities meant that in France the Nazis were not able to rely on the analogue databanks and were forced to identify and deport their victims through much less efficient means. The resulting difference was that in France the Nazis were unable to reach more than 20% of the Jewish population.

It was not until 1944 that the Nazis were able to identify René as a saboteur. He was then tortured and murdered in Dachau, one of the largest concentration camps in Nazi Germany. His torturer, Klaus Barbie, was saved by US troops and went on to lead a long life in South America. He would also be present at the murder of Che Guevara.

In the 1990s the French government processed a number of reports about the Second World War in order to include them in their national archives. Before this happened they were made available to the public. In one of these reports, René Carmille was declared a collaborator, which put his son Robert in the position of having to defend his father in the commentary sections of Le Monde.

Today René Carmille is celebrated by all who know his name as the first ethical hacker for his act of sabotage that saved tens of thousands of lives.

The End of the War

When the Allied troops liberated survivors from the concentration camps in 1945, they also found the IBM punch card machines. The data they recovered included statistics on inmates' capabilities for physical labour, capacities for resistance, “criminal” records, as well as suggestions for the manner of their execution.

In contrast to Coca Cola and other US companies who had huge business dealings with Nazi Germany, IBM was never sanctioned. By the end of the war they had become so closely interwoven with the entirety of German industry that they had made themselves indispensable, and were thus able to continue their operation without interruption. They were even compensated by the US government for the damage and loss of their machines. Thomas Watson was a personal friend of Franklin D. Roosevelt.

The extent to which Watson was aware of how the Nazis used his machines during the Holocaust is not known today. When Edwin Black uncovered the story in 2001, IBM denied him access to their archives. One thing is certain: through their collaboration with the Nazis, IBM was able to accumulate vast wealth, and for decades they held a leading position within the field of IT. After the war, they would develop systems to aid the Apartheid regime in South Africa.

Today, IBM has developed their own AI, Watson. It was presented to the public in the form of a friendly robot on the popular gameshow Jeopardy in 2013. The name is in reference to the founder of IBM, seen here drinking tea with Adolf Hitler before receiving a medal for his "Service to the Reich."

Patrick Derieg is a freelance IT technician from Linz, Austria, who deals with the history of IT and free software.

Originally published in German in "Die Volksstimme", issue No 11 in November 2023.

Comments ()