In the second segment of our November 2 publication, Andy Ramsay considers the quasi-legislation, surveillance and espionage that obstructs labour organising in the UK, and surveys steps towards resistance.

by Andy Ramsay

Cover photo by Constantinos Tsirides

Part 1 of this series can be found here.

Part Two: Hostile quasi-legislation through codes of practice and guidance

Statutory guidance

Beginning with the 1988 Employment Act, provisions started to be allowed in Acts of Parliament for the Secretary of State to issue codes of practice related to industrial relations. These codes of practice (CoPs) are listed as statutory guidance on the UK Government website. They constitute a very significant and worrying development. The CoPs are very detailed – much more detailed than legislation could be – but they are becoming the de facto law. It is doubly concerning because this law has not emerged from the normal process of legislature. It is law determined by the executive (i.e., directly by the Secretary of State).

Laypeople would make the common-sense assumption that guidance is only guidance and cannot be considered legally-binding. This assumption has been proved wrong in court a number of times. The most-commonly cited example of such a case is Rixon, R vs Islington. This case concerned a challenge to the adequacy of a local authority’s care plan for an individual with severe physical and learning disabilities. The legal issues presented included: (a) whether the care plan complied with statutory duties under the Chronically Sick and Disabled Persons Act 1970; and (b) whether the local authority had lawfully considered and applied relevant policy and practice guidelines in formulating the care plan. In relation to (b), the Courts held that: 'where there was a requirement to act under the general guidance of the Secretary of State’ then it was necessary ‘to follow the path charted by the Secretary of State’s guidance, with liberty to deviate from it where [it is] judged on admissible grounds that there is good reason to do so, but without freedom to take a substantially different course.'

This ruling would indicate that while it is described as guidance, it nevertheless has legal authority since, in almost all instances, it must be followed. Over recent years, other Acts of Parliament have created similar powers for such statutory guidance by the executive. A number of these acts have been related to trade union activities and there now exists a considerable portfolio of codes of practice (statutory guidance) that trade unionists need to be familiar with (and to comply with) if they want to act legally. These include CoPs on picketing, balloting for industrial action, balloting for recognition of unions, trade union executive elections, and Minimum Service levels during a strike. These are listed in Table 6 in chronological order.

Serious concerns have been raised about the government blurring the distinction between guidance and law; and purporting to use guidance to amplify (i.e., plug gaps in or clarify) legislation. Nevertheless, it would now seem that statutory guidance and codes of practice have become de facto legislation.

Table 6 also lists (in chronological order) guidance related to trade union activity that is not labelled as statutory guidance or a Code of Practice. This non-statutory guidance concerns activities such as: exercising citizen’s rights to bring court proceedings against unlawful industrial action; unjustifiable discipline by a trade union; trade union membership; payment of union subscriptions; trade union funds and accounting records; blacklisting of trade unionists; industrial action by trade unions; trade union political funds; and issuing work notices in relation to Minimum Service Levels during industrial action. Most laypeople, after learning that statutory guidance was legally-binding, would probably assume that non-statutory guidance was therefore NOT legally binding – the word ‘statutory’ being what distinguished legally-binding from non-legally-binding.

Case law (judge-made law) would now suggest that, while non-statutory guidance is not legally-binding, acting contrary to non-statutory guidance may be difficult to defend in court. In Ali vs London Borough of Newham EWHC (30 October 2012), the High Court ruled on the status of a piece of non-statutory guidance. The Department for Transport had produced national non-statutory guidance on the use of tactile paving to assist the visually impaired. The national guidance was developed in conjunction with, and with the endorsement of, Guide Dogs for the Blind and the RNIB (Royal National Institute for the Blind). The London Borough of Newham had developed its own guidance, which diverged from the national guidance. Because the national guidance emanated from the executive, with the input of independent expertise, the court ruled that it had to be followed. Case law now seems to have established that we may be bound by guidance because it is authoritative and expert, rather than because it is labelled as statutory.

In the documents listed in Table 6 there is explanatory text in both the codes of practice (statutory guidance) and guidance (non-statutory Guidance) regarding their relevance to court proceedings. This text would seem to support the conclusions drawn above.

The introduction to the latest version (March 2024) of the ‘Code of Practice: Picketing’ contains the following paragraph:

The Code itself imposes no legal obligations and failure to observe it does not by itself render anyone liable to proceedings. But statute law provides that any provisions of the Code are to be admissible in evidence and taken into account in proceedings before any court, employment tribunal or Central Arbitration Committee where they consider them relevant.

The introduction to the latest version (November 2023) of the “Guidance. Minimum Service Levels: Issuing work notices, a guide for employers, trade unions and workers” contains the following paragraph:

This non-statutory guidance gives general guidance only and is not a substitute for professional legal advice. Courts and tribunals may choose to consider the views of the Department for Business and Trade in this guidance where they consider them relevant, but this is for courts and tribunals to decide. Only courts and tribunals can give authoritative interpretations of the law.

In an atmosphere of state, police and judicial hostility to industrial action, or lack of public sympathy for disruptive strikes, it will likely be difficult to mount a successful defence against non-compliance with the statutory, or non-statutory, guidance in courts.

This new form of executive law, while initiated by John Major’s government, was heavily used by the New Labour governments of Blair and Brown and picked up again by Rishi Sunak’s Conservative government.

Table 6. Government codes of practice (statutory guidance) and other Government guidance relevant to industrial relations and listed on UK Government website.

Date of first publication (latest update), Prime Minister, Party |

Codes of Practice (Statutory Guidance) and other Guidance. |

Useful links |

31 March 1992 (11 March 2024) John Major Conservative |

Statutory Guidance Code of Practice: Picketing Guidance on picketing for employers, workers and members of the public who may be affected by a picket or any associated activities. |

|

8 May 2005 Tony Blair Labour |

Guidance Guidance: Industrial Action and the Law Citizen’s Right to Prevent Disruption. |

Industrial action and the law: citizen's right to prevent disruption - GOV.UK |

1 Sept 2005 (24 Feb 2017) Tony Blair Labour |

Statutory Guidance Code of Practice: Industrial action ballots and notice to employers. Practical guidance to trade unions and employers to promote the improvement of industrial relations and good practice in the conduct of trade union industrial action ballots. |

Code of practice: industrial action ballots and notice to employers - GOV.UK |

5 Sept 2005 Tony Blair Labour |

Statutory Guidance Code of Practice: Access and unfair practices during recognition and derecognition ballots. Guidance on the statutory procedure for recognition and derecognition of trade unions for the purpose of collective bargaining. |

Code of practice: access and unfair practices during recognition and derecognition ballots - GOV.UK |

8 May 2006 Tony Blair Labour |

Guidance Unjustifiable Discipline By a Trade Union. Guidance on what is meant by unjustifiable discipline by a trade union |

|

8 May 2006 Tony Blair Labour |

Guidance Union Membership: Rights of members and non-members. Employment law gives employees basic protections against being penalised for being, or not being, members of a trade union. |

Union membership: rights of members and non-members - GOV.UK |

8 May 2006 Tony Blair Labour |

Guidance Payment of union subscriptions through check-off. Guidance for employers on ensuring deductions they make are lawful, and the remedy available to workers from whom deductions are unlawfully made |

|

8 May 2006 Tony Blair Labour |

Guidance Trade union funds and accounting records. Guidance for trade unions and their members about statutory rights and duties in relation to union funds. |

|

9 April 2009 Gordon Brown Labour |

Statutory Guidance Trade union executive elections: guide for trade unions and their members. Describes the statutory requirements which apply to trade union elections. |

Trade union executive elections: guide for trade unions and their members - GOV.UK |

2 March 2010 Gordon Brown Labour |

Guidance Blacklisting of trade unionists - guidance. Guidance on the Employment Relations Act 1999 (Blacklisting) Regulations 2010. |

|

9 April 2010 Gordon Brown Labour |

Guidance Industrial action and the law. Guidance for employers, trade unions and workers on industrial relations law. |

|

9 April 2010 Gordon Brown Labour |

Guidance Industrial action and the law: guide for employees and trade union members. A guide to the statutory rights and protections given to those who take industrial action. |

Industrial action and the law: guide for employees and trade unions members - GOV.UK |

9 April 2010 (22 Feb 2018) Gordon Brown Labour |

Guidance Trade union political funds. Guidance on how a trade union political fund must be operated. |

|

16 Nov 2023 Rishi Sunak Conservative |

Guidance Minimum service levels (MSL): issuing work notices. Guidance for employers, trade unions and workers on issuing work notices in relation to minimum service levels during strike action. |

|

6 Dec 2023 Rishi Sunak Conservative |

Statutory Guidance Reasonable steps to be taken by a trade union: code of practice. Guidance for trade unions on “reasonable steps” in relation to minimum service levels. |

Reasonable steps to be taken by a trade union: code of practice - GOV.UK |

Part Three: Surveillance and espionage by security services

In addition to the legal instruments described above, the state has also conducted clandestine espionage through the police, security and intelligence services. The Undercover Policing Inquiry, an ongoing public inquiry into the conduct of undercover police operations, was commissioned by Theresa May in 2015. It has been heavily criticised for the excessive time taken to conduct investigations and the anonymity granted to many police officers giving evidence. The Guardian has reported that as of 2023 the inquiry had cost the public in excess of £50m and ‘performed to perfection in its dual function of creating the illusion of a political response, while firmly kicking the issue into the long grass’. As of 2018, the Inquiry had identified more than 40 organizations (mainly left-wing, animal rights or climate change activist groups or political parties) which had been infiltrated by undercover police or quasi-police agents working for a private company sub-contracted by Whitehall.

The Covert Human Intelligence Sources (Criminal Conduct) Act 2021 makes the provision for the use of undercover law enforcement agents and covert sources and the committing of crimes in the undertaking of their duty. In 2020, the Institute of Employment Rights referred to the then Bill, as introduced by Priti Patel, as ‘the Bill that gives MI5 carte blanche to spy on trade unions’.

This, of course, is nothing new. That police and intelligence services had infiltrated major trade unions, and most likely caused strikes to fail, has been known for decades. Joe Gormley, the leader of the National Union of Miners (NUM) and Ray Buckton, the leader of the Associated Society of Locomotive Engineers and Firemen (ASLEF), were both allegedly Special Branch informers. The identity of a spy from the Special Branch, codenamed ‘Silver Fox’, who infiltrated the NUM and provided critical intelligence that allowed the Miners’ Strike of 1984–85 to be beaten, has not been disclosed to date. MI5 have confirmed that they targeted trade union leaders during the strike.

Part Four: ‘Do Not Resuscitate (DNR)’or ‘Come Out With All Guns Blazing’?

It is difficult to feel anything but despondency having reviewed the lawfare campaign against the labour and trade union movement. Not only has it been brutal and relentless, it has been successful in making them almost completely irrelevant. As a result, any semblance of democracy has withered on the vine. The UK lurches towards authoritarianism, negation of free speech, suppression of peaceful protest, and government pandering to the will of the far-right, both domestically and internationally.

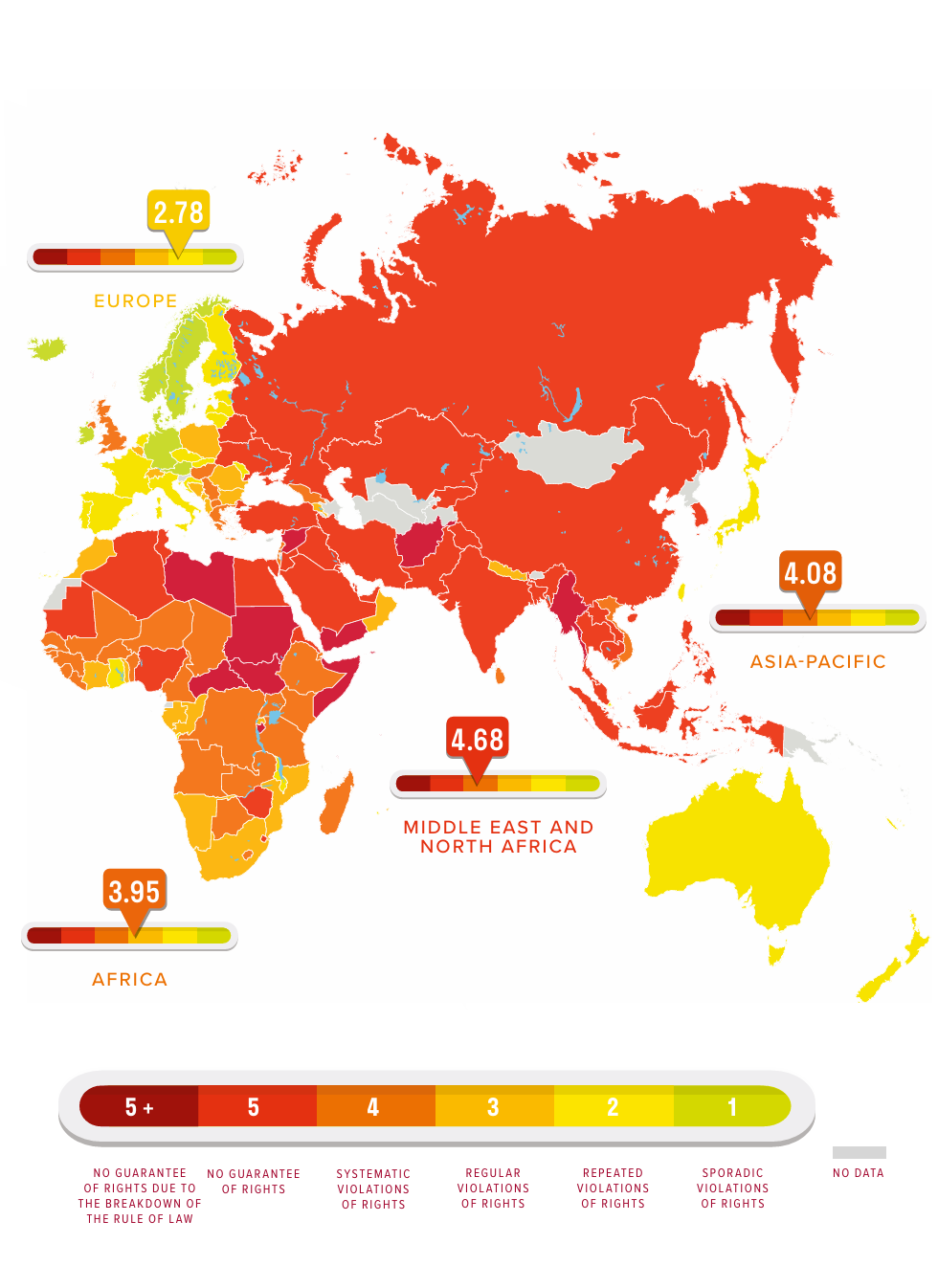

The International Trade Union Confederation (ITUC) has recently released the 12th Edition (2025) of the ITUC Global Rights Index. It is described by the ITUC as ‘the only comprehensive, worldwide annual study of the violation of workers’ rights – freedoms that form the basis of the democratic rule of law and fair working conditions for all’. Countries are assigned ratings from 1 to 5, with an additional category of 5+ where there is no guarantee of rights due to breakdown of the rule of law. In 2025, the latter group comprises 12 countries including Afghanistan, Myanmar, Palestine, Sudan and Yemen. Ratings and descriptions are presented in Table 7.

Table 7. ITUC Global Rights Index. Ratings and workers’ rights

Rating |

Description |

1 |

Sporadic violation of rights |

2 |

Repeated violation of rights |

3 |

Regular violation of rights |

4 |

Systematic violation of rights |

5 |

No guarantee of rights |

In the 2025 study of 152 countries, there were: 7 countries with a rating of 1; 23 with a rating of 2; 30 with a rating of 3; 41 with a rating of 4; and 39 with a rating of 5. The average regional ratings were: 2.78 for Europe; 3.68 for the Americas; 3.95 for Africa; 4.08 for the Asia-Pacific; and 4.68 for the Middle East and North Africa.

The UK (with a rating of 4) currently has the worst rating in western Europe. See report for details. Its rating is also worse than the average regional rating of any region of the world except for the Middle East and North Africa.

The UK’s rating and basic description is accompanied by additional text: ‘Workers in countries with rating 4 have reported systematic violations. The government and/or companies are engaged in serious efforts to crush the collective voice of workers, putting fundamental rights under threat’.

Even more insidious than the relentless lawfare against labour organising in the UK is the underfunding and undermining of processes for workplace justice by successive Conservative and Labour governments. Employment Tribunals are a key part of arbitration when employers and employees cannot settle grievances and disputes. As of March 2025, there were 491,000 claims for Employment Tribunals open. There is currently a waiting list of over one year for them to be heard. A lack of funding and a shortage of qualified judges are cited as the reasons. Even those workers who are awarded compensation are let down – with many never receiving the money they were supposed to receive. A special government scheme which was set up to ensure that people receive their awards is failing. Three-quarters of the 7,000 workers who won awards at tribunals and who enlisted in the scheme have still have not received their payments. The Conservative Government introduced the Employment Tribunal Penalty Enforcement and Naming Scheme in 2016. According to it, companies face a penalty if they don’t pay the workers the compensation within 28 days. Since 2018 the offending companies would also be named online. Although over 4800 penalties have been issued, records show that only around 100 of these penalties have been paid. No company has, to date, been named.

The current Labour Government’s Employment Rights Bill 2025 is at present in the ‘ping-pong’ stage when it goes back and forth with amendments between the House of Commons and the House of Lords. Following that, it will proceed for Royal Assent before passing into law. Many trade unionists expect the final Bill to be considerably reduced, through amendments, in relation to its original form. It would in any case represent minor gains in trade union rights relative to the rights lost by trade unions over the past 50-odd years.

Given the powerlessness of the trade unions in the UK now, it is difficult to see what leverage we have for reasserting ourselves and repossessing the rights that have been taken from us. There have been longstanding campaigns focused on regaining our rights and freedoms, such as the Campaign for Trade Union Freedom in the UK. It was established in 2013 through a merger of the United Campaign to Repeal the Anti-Trade Union Laws and the Liaison Committee for the Defence of Trade Unions. Its constitution was revised in 2023. By virtue of the time that these campaigns have been operating and the continued lawfare against trade unions detailed in this article, I would respectfully conclude that they have failed.

Is there any point in trying to fight back from such a dire position? Do we label ourselves with a DNR badge and allow a natural death? If we do, we betray the millions of workers who fought for these rights through generations. We betray the millions of workers around the world who continue to fight for their rights.

We need to fight. We need to come out with all guns blazing. We need to find a new way.

This article allows us to see clearly what rights we have lost. It allows us to see what we need to demand in order to return to the position we were in 55 years ago. It will allow us to monitor the progress of the campaign that we build to seize them. The Campaign for Trade Union Freedom in the UK and similar initiatives show us that it can’t be done by passive campaigning. The working people of the UK need to know what rights have been stripped from them by stealth. Mass mobilisation of workers to protest against these appropriations is needed. And, of course, the objective should not be to return to the 1970s; it should, at the very least, start from understanding our failures, building upon them, and establishing strong, embedded institutions that are capable of responding to the demands of a precarious, fragmented class.

Direct action. Civil disobedience. It can be done. It is up to us. Unions begin with ‘U’.

Andy Ramsay is Scotland Area Organiser for the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW).

This article will also be published in the IWW's Wobbly Times newspaper.

If you would like to contact Andy or the IWW in Scotland you can do so at the following email address: scotland@iww.org.uk

Comments ()