Remembering the Radical Nurses Group

The Radical Nurses Group was established in the 80s and was active throughout that decade. As a small grassroots collective, they were able to form bonds of solidarity and support within their profession, taking a strongly political stance to work and the conditions it creates.

By Sam Button

The Radical Nurses Group was established in the 1980s and active throughout that decade. The grassroots group of activist-feminist workers was small, but was able to form bonds of solidarity and support within their profession, taking a strongly political stance to their work and the conditions that were created from it. They engaged in direct action, agitation, rallies and work-ins, including the occupation of hospitals across London. Around 30 people were members of the Radical Nurses, this included some male nurses but mainly female. Whilst not exactly a trade union, they were always an informal group, positioning themselves to the left of their trade unions on many issues and especially in terms of direct action.

I am sitting in Dunoon Burgh Hall interviewing Elspeth Campbell, a former member of the Radical Nurses Group, who was involved throughout the 80s. Her activities included radical action such as occupying a hospital ward. This kind of action would be unheard of in the current political landscape of the NHS, but in the 1980s things were different. Elspeth cut her teeth in nursing in some of toughest political and economic times the UK has faced, beginning with austerity imposed by the IMF in the late 1970s, to the Thatcher era of political and trade union repression. With the recent strikes of doctors and nurses across England and Wales, I was interested in gaining Elspeth’s perspective as someone who was involved in radical direct action in the health service, perhaps to glean some lessons for the current movement of more politicised health workers. The impression I get of her is one of quiet dignity, compassion and a genuine commitment to improving the lives of others. Elspeth also volunteered with young homeless women and was active in the Workers Revolutionary Party, later going on to become a social worker.

Elspeth came from a socialist background – her parents met on strike at Royal Mail. ‘There was no strike money, just pennies, they had to sell the car’. Her parents had no income for two months when she was growing up. ‘They were out again after two months, but that was the longest time they were on strike’. However, even in these circumstances, people came together. ‘You’d open the door and there’d be a parcel there of food or a box, and you don’t know who it came from. People just dropped stuff off because they knew that they were striking. A woman made a dress for me! She knew I was leaving primary school, and I had a leavers thing’. Mutual aid abounded in their community. ‘The best thing was, somebody left me and my brother a long box full of sweets. I’d never seen so many sweets before!’. It was because of this background she never considered working for a private company.

‘I wanted to be an engineer, but my careers advisor said, “nursing or secretarial work”’. In school she excelled at biology and anatomy, and so chose nursing. After training in Greenock School of Nursing, Elspeth left Scotland for London. A local to Argyll and Bute, Elspeth tells me that she left home because it was the first year that there were simply no local jobs for her cohort to go to. ‘All the tutors said, it was the first time they’d experienced this, there were no jobs’.

Elspeth began her nursing tenure in 1979 as an agency worker across various London Hospitals, just as Margaret Thatcher swept to power. It’s notable that agencies were being used at the time, highlighting that causalisation and precarity of essential workers are an enduring problem. Elspeth wanted to work in the Health Service; ‘never any private work. Even when I was doing agency work, it was within the Health Service’. ‘I could have gone to the Wellington and earned three or four times as much, but I wouldn’t – that’s my principles’. These principles were forged by the mutual aid and class solidarity that she witnessed growing up.

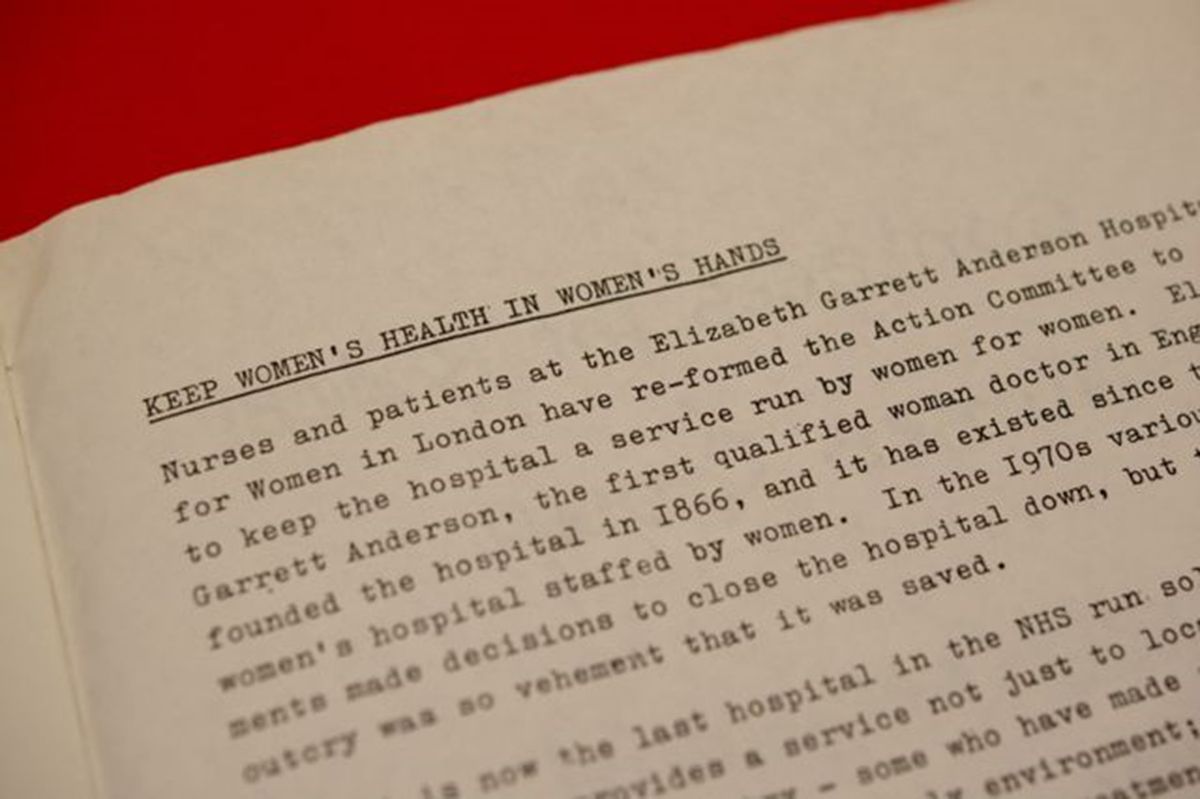

She then worked for Brent Health Authority, in Central Middlesex Hospital, the Royal Free Hospital, St Mary’s Hospital, Elizabeth Garrett Anderson and Obstetrics Hospital (EGA). The EGA was named after Elizabeth Garrett Anderson, one of Britain’s first female physicians, and had an ethos that reflected the early radicalism of Anderson: healthcare by women for women. Throughout the 1980s, there were attempts to close EGA, or to convert it into a day unit, which eventually did happen, merging it with University College Hospital.

Trade Union Activism and The Radical Nurses Group

Elspeth was a shop steward and health and safety representative with the National Union of Public Employees (NUPE), which later merged with NALGO (the National and Local Government Officers Association) and COHSE (the Confederation of Health Service Employees) to become Unison. Much of her time in the 1980s was spent dealing with hospital administrators, who were changing the dynamic of healthcare in the UK. Whereas previously a board of health professionals (made up of head surgeons, nurses etc.) had administered the hospital, instead, administrators ran the hospital, making key budgetary decisions. Power was taken further away from the professionals who worked at the hospital into the hands of an administrative class, the heads of whom were beholden to government health ministers.

The Radical Nurses Group was an informal offshoot of the union, as ‘we felt they weren’t radical enough’. ‘The Radical Nurses Group wouldn’t just accept the position of the union office. A lot of the time the guys in the union office were going out for drinks with the managers. They’re doing negotiations in the pub, then they come back and pretend they’re giving you a deal’. This ‘boys club’ attitude reflected the entrenched patriarchal attitudes of the trade unions in those days; Elspeth also notes the lack of women in any of the union offices.

‘I would refuse to negotiate, because I knew things were going on behind the scenes. I would always go in with improvements [to offers] because I wouldn’t negotiate for anything less: all that came from being in the radical nurses group’. Whenever a representative from the union office would go to speak, members of the radical nurses would challenge them, ‘especially when it was RCN!’. This kind of dogged approach pushed the unions to engage in more radical action, and therefore better deals for the workers. All of this was borne out of the commitments of the Radical Nurses.

Setbacks: Thatcher’s Union-Busting Laws, Regrading & Managerialism

However, this era of quick, responsive direct action would not last. ‘What they did then was bring in restrictions. Thatcher brought in that you had to give 78 hours’ notice if you’re going to have a union meeting; you can’t have it in your workplace,’ along with a laundry list of union busting laws. ‘So it got harder and harder’. This noticeably slowed the reactivity of organised workers within their union.

Another setback at the time was regrading. Nurses working at the time were subject to clinical regrading, which had been protested at the time of its introduction. ‘That was another smoke and mirrors thing’. Elspeth says that regrading was a ploy to ‘shut us up, because of the general nurses strike,’ referring to the nurses strike of 1988 over regrading, low pay. ‘Nurses were becoming more militant, more aware, so they introduced the regrading’. ‘It was the most unfair thing’. Each hospital had its own budget, so they couldn’t give everyone the grade they deserved. One had to be interviewed for regrading. Whereas Elspeth was moved up a grade for ‘slightly better pay’, a far more experienced but part-time colleague was moved to a grade below Elspeth: ‘it was punishing part-time workers. It was supposed to acknowledge their years of experience, their training, and she’d done far more than me’.

‘We managed to get it to the stage when we had the general nurses strike, we had several strikes, and we had the big marches’. This was the era of mass political action in the NHS, which we are again seeing echoes of now. ‘The media kept saying there was infiltrators, they weren’t all nurses’. This was perhaps because of the presence of men within the RNG, but Elspeth and the other members knew this was nonsense concocted by the media. This was in the wake of an era marked by increasing paranoia within the labour movement about Trotskyist infiltration from the Militant tendency.

‘They were continuing the hospital closures and the regrading, and it was hard, because I’d arranged for a walk-out, and then the union office wouldn’t back it. It was to do with the regrading, and they were saying “no, it’s got to be a national thing” but nothing was happening nationally. So, I and other shop stewards thought “we’ll all do it within our own groups” because it would have been easier to organise, to have that fightback, but they weren’t for it’. ‘I was a bit naïve then, I should’ve just went for it, but I didn’t. Because you were told by your union office “it’s not gonna work…”’. A new HIV unit had been opened, which was then threatened with closure, because there was no money to staff it, ‘so it was flying pickets, we’re going out to support the new HIV unit’. The bravery of the RNG and other workers in defying their unions, thinking and organising quickly led them to a slew of action, highlighting the detachment of union officials from the political will of the time, and the tepidness of larger mainstream trade unions.

The Griffiths Report (released in 1983) had promoted the idea that problems with the NHS could be solved by managerialism, and was written by Monsanto and Sainsbury’s executive Roy Griffiths. ‘It was using the model of how Sainsbury’s was run, and it was all about making money, making profits’. Administrators were the agents of this managerial approach. ‘You were constantly battling to keep the status quo. When you were doing your ordering, it would have to go through the administrator’. This delayed patient care and limited the amounts of things that could be ordered, filtered through the opinions of administrators who had no medical training. ‘They wouldn’t listen to you, you couldn’t discuss anything with them’. That took up a lot of Elspeth’s time. Furthermore, only around six out of 200 administrators were women.

Being in the radical nurses challenged many of the patriarchal notions of nurses as silent and respectable workers, and Elspeth found her experience with them an empowering one. The Group had initially focused their attention on Soho Hospital (for Women), because they knew of Thatcher’s plan to close it and merge it with EGA, but suspected that EGA would be next on the chopping block of closures if this happened. Women’s health has never placed highly in people’s agendas, which was reflected in the fact that there were only three women’s hospitals open in London at the time. There was no perceived rationale for closing the Soho Hospital, but the Tories claimed that it was too expensive to keep both Women’s hospitals open.

Thatcher was going to keep the day unit at Soho, which was subsequently moved to EGA. That meant that for the first time there were male surgeons at Elizabeth Garret Anderson, which had previously had an all-female staff. The Hospital for Women in Soho Square was merged with EGA in ‘89. Elspeth pointed out that none of the money from the sale of the hospital went back into the NHS, and its location at Soho Square made it prime for development. This was closed despite containing being a Centre of Excellence for women’s health, which Margaret Thatcher herself acknowledged in a visit to the hospital; ‘We knew Thatcher was coming to Soho, so we planned a meeting. On the news it was saying she was in Germany, but we had inside information. When she arrived, she was on the news saying how wonderful it was, this was just before she shut the hospital.’ The hypocrisy of the Tory government was laid bare for Elspeth and her comrades. ‘We were sitting there watching this saying “you’re fucking shutting it!” and within a couple of months it was shut’.

When EGA was operating, all the staff were women, which was radical in and of itself. ‘Whether they were electricians, cleaners, surgeons: they were all women […] if a social worker was brought in, it was a woman, any counselling, it was women. It was different. It was totally different’. This all-women environment fostered a more politically radical climate too, ‘The nurses that wanted to work in a women’s hospital were more radical, politicised; felt strongly that that hospital should exist and women’s needs were met’. Elspeth claims that this environment led to better care for the women patients, who did not face judgement and scrutiny that women often face when seeking medical treatment in a patriarchal system of medicine. ‘It just seemed more in tune, more caring. It was a lovely place to work’. Elspeth pointed out that gynaecology tended to be a male dominated field of medicine, so care coming from women really made a difference: ‘for women that were terrified coming in, a lot of emotional needs were getting met’.

The occupation of the University College hospital ward

At the time they were closing Soho, they were closing other London hospitals as well. It was in this climate of austerity and public sector service cuts that Elspeth and other became radicalised. University College Hospital had closed down a ward unexpectedly and suddenly. The Radical Nurses worked together with Class War, Red Action and a number of other radical left groups to keep a presence in the ward. The Radical Nurses and their comrades maintained a presence in the ward of ‘about half a dozen’ people at any time, and incredible commitment to keeping public services alive. Elspeth cheekily explained that ‘The only way that you could get in was to go ‘round the side, and up on to the bins, and there was a wee window that we managed to keep open. I don’t think they realised for a long time’. There were also plans to close another ward, and they had banners out the window, so that people could see and know that another ward was being slated for closure. ‘Direct action is obviously a good thing, to be out and be visual’. Using the occupation to highlight other struggles was a brilliant tactic, and one that was essential for informing the wider public. The occupation and work-in lasted several months, and although the activists were forced to leave ‘it went on for a good while before they got stopped’, keeping services open for those who needed them.

Reflecting on the radicalism of the RNG: Lessons for now

The Radical Nurses disbanded in the 1990s; ‘from the 80s to the 90s, it slowed down, fightbacks slowed down’. The Archive of the Radical Nurses Group sits in the Royal College of Nursing in Edinburgh. This is ironic given the reputation of the RCN as a conservative trade union, and one that frustrated Elspeth when she was a nurse. Despite its reputation, the RCN recently voted to strike again in the 2023, after a round of action the previous year. Yet Elspeth sees the overall landscape of the profession as much less radical than it was.

‘You had Blair coming in and people thought “this is going to be wonderful! Things are going to change, things are going to be nationalised” because Thatcher started the privatisation of the NHS in the 80s. Privatising all the ancillary staff, the cleaners, the kitchens. That was a big bulk of privatisation’. Like casualisation, the privatisation of the NHS is not something to be thought of as a contemporary problem, having its roots in the Thatcher era that the Tories of today are parroting. ‘Now, I think it’s good that the doctors are out’. However, Elspeth seems to believe that less people are willing to change the system, and more people simply trying to work within it. ‘I think more staff, when they’re coming out of their training, are looking at climbing the ladder than practical nursing’.

‘I think everybody’s generally less radical. You know, it’s this consumer society, it’s all about owning things, having your mortgage. People are so wrapped up in that. I feel we were much more radical, but it’s good to see that the Doctors have come out, because the hours they do and the money that they get is just crazy, absolutely crazy’. From Elspeth’s perspective, there has been a sea change in our society. Some of this has to do with the structure of the economy, ‘in the early 80s, 78% of the population worked for a public service. Only a small percentage worked for private companies and industry; it’s all turned around now. People are working for private companies that are paying less than what public services were. Whereas before public services were seen as [paying] less money, but you had a job, more job security. Whereas now, people don’t even have contracts’. Elspeth says that it’s got a lot more difficult to get people to go out on strike, especially with the media constantly repeating a denigrating line about trade unions. In her own workplace, no one is in a union, compared to historically all the workplaces in previously were unionised. Additionally, she believes that ‘there’s not that collective that there was before’. It seems that more and more, we are all Thatcher’s children: individualistic and unwilling to change the broken neoliberal system which pervades around us.

It seems important, therefore, that workers have the conversations which lead them to organise and unionise. Not only this, but to not accept the systems that are being imposed by managers, but fight to change it and challenge the status quo. The lesson of the Radical Nurses Group is also not to accept the leadership of large, professionalised trade unions, whose timid conservativism leads to a lack of direct action. The RNG showed that radical, direct, grassroots activism is the only real way to resist austerity and public sector cuts. What I find particularly inspiring is the quick adaptiveness and ability to improvise that led to responsive direct action by the RNG. No matter what barriers are placed in the way, solidarity and a disregard for authority, be it from management, anti-union laws or unions themselves, should be the way forward for activist workers looking to take back control.

Sam Button is a member of the Interregnum collective

Comments ()