In this talk delivered as part of the University and College's Union Political Education Programme, Chris Reid discusses a series of radical texts produced by workers in mid-20th century America, and the hopes of overcoming capitalism that they contained.

By Chris Reid

This talk was delivered to the Glasgow University branch of the University and Colleges Union (UCU) as part of its newly established Political Education Program. It was given on November 27, 2024 by Christopher D. Reid, who also facilitated a follow-on group discussion.

The first part of this talk will be like a deluge of events, persons, cities, and organisations. I do this intentionally. For it is how the tide of labour unrest and organisation must have seemed to many Americans in the 1930s, as they got news of what their fellow workers were up to through rumours, gossip, and newspapers. These upheavals must have had a similar effect on the minds of writers sympathetic to the cause of working people.

What was that cause? It certainly varied by race, gender, location, industry, and job. But it is safe to say that President Roosevelt’s rhetorical flourish of a New Deal struck the right chord. There was a sense among most working people that they were taking the brunt of the economic tribulations caused by the Great Depression. Many – not all – also believed that trade unions were the best way for them to stand up to the bosses – who were still getting richer – and to get fair wages and reasonable working conditions.

And with that, let us dive into the deluge.

In June of 1933, President Franklin Delano Roosevelt signed the National Industry Recovery Act into law. It was the first of the New Deal legislation that he would push through Congress. The New Deal was meant to not only do something about skyrocketing unemployment, but also to substantively expand the welfare and regulatory state in America.

From the perspective of workers, the most important and celebrated part of the NRA was section 7(A) which, for the first time in law, gave employees the right to ‘organize and bargain collectively through representatives of their own choosing’.

Today, we take the right to join a union for granted. But for the American worker a hundred years ago, joining an independent trade union was a risky business. In the 70 years before the passage of the NRA, Americans had been organising on shop floors, steel furnaces, railways, coal faces, and sharecropper fields. They were determined to protect their rights as workers. Industry was every bit as determined to stop them from doing so.

The early years of labour organisation were some of the bloodiest and most violent in American history, as industry attempted to bust unions wherever they appeared. In the decade or so before the Great Depression, many companies had come to terms with the reality of trade unions and, to keep the peace, decided to negotiate with their workers through them. However, this was not universal, nor was it legally required. Section 7(A) changed all that.

The American Federation of Labor (the AFL) had become the most powerful national union, in that it had a salaried and experienced staff of labour organizers. Whenever workers in a particular company wanted to organise, they tended to ask the AFL for help. This the latter did, and the newly organised shop would become a local affiliate.

After the passage of the NRA, the AFL issued an appeal to unorganised workers to join and form trade unions in order to secure the benefits of the new law. It also warned them not to be ensnared by company unions – mere organs of managerial control over wage earners.

But the people – ordinary workers – did not sit around waiting for this appeal. When the NRA was passed, they knew what it meant and sprang into action immediately.

One San Francisco dressmaker by the name of Jennie Matyas was recorded as saying, ‘When the NRA was passed, I suddenly came to life and thought, “My God, I wish I were back in the movement now”’. She soon rejoined the International Ladies’ Garment Workers’ Union.

On June 22nd of 1933, an organiser for the United Mine Workers in traditionally anti-union Kentucky, home to extensive coal fields, wrote, ‘The people have been so starved out that they are flocking into the Union by the thousands…I organized 9 locals Tuesday’. When company police ordered his men off the premises, the same organiser went on to say that ‘we had the meeting anyway, with about 2000 people present’.

In the two years after the passage of the NRA, a growing insurgency emerged in the AFL. Many labour organisers believed that it was not taking full advantage of the new union law. John L. Lewis of the United Mine Workers led this group of dissenters. He believed that unions should organise along industrial lines so as to better match and check the power of the bosses in each industry.

To make a long story short, the AFL convention of 1935 ended with Lewis punching another labour leader in the face and him and his acolytes storming out of the convention hall. That year, they would formally split from the AFL and rename themselves the Congress of Industrial Organizations – the CIO.

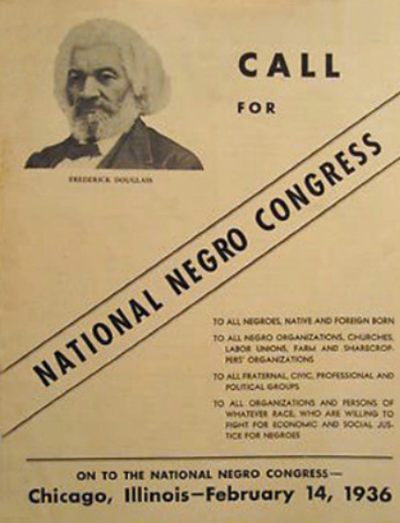

In this same year, 1935, a group of Black intellectuals, civil rights activists, trade unionists, and communists organized a conference at Howard University. The purpose of the conference was to solve the economic problems of Black people and to fight for the right of Black workers to access New Deal benefits. As it stood, the New Deal was a Raw Deal for Black people, as the NRA still allowed for race-based differences in wages and working conditions. This conference led to a series of further meetings and conversations that sought to join up civil rights and economic rights. Defeating state-sanctioned racism was inseparable from the full participation of Black workers in trade unionism. This idea would lead to the establishment of the National Negro Congress (NNC) in 1936.

As I intimated above, the NNC – which I think should be called the Black Popular Front – was composed of intellectuals, artists, civil rights activists, trade unionists, communists, socialists, and others dedicated to radical change in America. Its primary aim was to defeat white supremacy; and it viewed Black worker activism as the most effective means of doing so. The NNC, like other popular front organisations, was willing to form coalitions and alliances with like-minded groups to achieve its goals. It joined forces with the CIO to do so. And I only have time to give you one example of this collaboration.

The NNC, along with the CIO, fought a three-year battle, from 1936–1939, to unionize Chicago’s steel and meatpacking industries. In addition, the NNC launched a campaign centred on getting city jobs for Black workers, stopping police brutality, and accessing New Deal benefits for Black people. The movement consisted in large part of mass meetings, pressure campaigns, and strikes. And its lasting successes included opening up wartime factory jobs to Blacks and desegregating skilled employment jobs on Chicago’s local transit system. Moreover, Chicago – Red Chicago as this historical period is sometimes known – stood as an example to two general audiences. To traditional Black civil rights leaders, such as those in the NAACP, it proved that labour-based civil rights activism worked. To white labour leaders, it demonstrated that expanding trade unionism to include Black workers could strengthen the industrial labour movement.

This was certainly an extraordinary time in American history. And I think the work of creative writers helps us make sense of the upheavals and lays down markers for how artists can engage with worker activism – especially if they come from among those they strive to represent in fiction.

Of the books I will discuss today, all but one were published between 1930 and 1960. I must note that many of the writers were actually part of the grassroots struggles they wrote about and could only record these events years later. Indeed, some of the most celebrated fiction from the 30s was not published until the 70s; such was the case of the brilliant Tillie Olsen and Meredith Le Seuer. There was also the state-driven crackdown on communists that started in the twenties and has never really let up. I have selected this period because it falls within the late stage of the Old Left, just before the birth of the New Left. What follows consists of stories about resisting oppression, organising workers, and arguing for civil and economic rights. The stories all have trade unionism at their centre.

This is key. Capitalism and white supremacy, as creeds and doctrines, are the most powerful structuring forces of modernity. They were so in the mid-20th century and they remain so now. The union movement, as a response to capitalism at least, is also a structuring force of modernity and is likewise here to stay. Recent events suggest we may be moving toward a new world shaped by new underlying forces. But trade unionism will still be with us. Organised labour – that is unfortunately unorganised politically – will continue to be a political force in America. The stories we tell about worker agitation and the ways in which we give voice to working people will continue to matter.

As I mentioned, I have put the fiction of this period into three rough categories: resistance, organising, and argument. I did this for convenience – to make literature relevant to activism. But rather than come up with some abstract explanation of how each novel falls under the category I have assigned it, I will let the stories speak for themselves.

Resistance

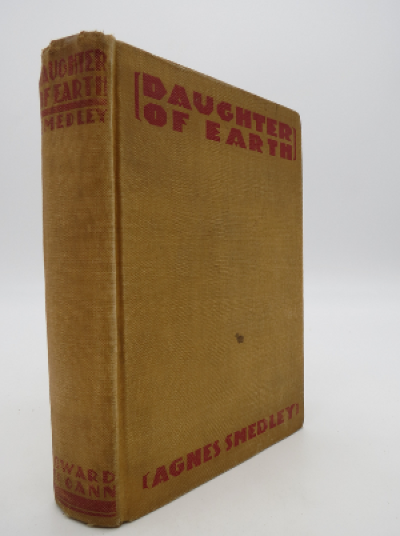

Under the category of resistance goes Daughter of Earth by Agnes Smedley and Youngblood by John Oliver Killens.

First, Daughter of Earth.

Agnes Smedley was born in Missouri in 1892, into extreme poverty. This book, published in 1929, is without doubt autobiographical, in that it weaves aspects of Smedley’s personal life into the Odessey of the main character.

The story is told in the first person. Its protagonist, Marie Rogers is, like Smedley, born into rural poverty in northern Missouri at the end of the 19th century, becomes an itinerant worker, educates herself, becomes a school teacher for a while, drifts from one mining town to another, joins various trade union and socialist movements, and, at the end of the novel, becomes part of the Indian nationalist movement in America. Throughout it all, Marie forges her own politics of socialism, feminism, and internationalism.

Now what I find most striking about this novel is the indomitable will of Marie Rogers to defy all attempts by anyone to exercise arbitrary power over her. From very early in the story, she is presented as a loving daughter to her parents and sister to her siblings. But she fights mistreatment by her mother, who is worn down, frustrated, and embittered by poverty. In what must have been shocking to the readers of the day, Marie mocks Christianity and the lessons she is taught at Sunday School. And she adamantly refuses to get married. Her hatred of marriage is potent, enduring, and is one of the persistent themes throughout the novel. But this hatred is grounded in sound reason. It is perhaps best summed up in this wonderfully poetic passage:

Had it not been for the wanderlust in my blood—my father’s gift to me—and had I not inherited his refusal to accept my lot as ordained by God, I might have remained in the mining towns all my life, married some working man, borne him a dozen children to wander the face of the earth, and died in my early thirties. Such as the fate of all women about me. But settled things were enemies to me and soon lost their newness and colour. The unknown called.

Marie is not the only woman in open defiance of what society expects of them. Her Aunt Helen, a sex worker, proudly plies her trade; and tells Marie’s father (Aunt Helen’s brother) in no uncertain terms that the entire family would be destitute if it wasn’t for her sex work. This is another busting of convention: the prostitute is neither ashamed nor victimized by her work but carries it out proudly and is portrayed as a balanced and well-adjusted human being.

Though Daughter of Earth was written before the Great Depression and the worker activism of the 30s, I chose it because it gives a sense of the widespread trade union and progressive activism that was already astir in the country before the 1930s. It is also an excellent example of oppositional writing among women authors of the time.

Next, Youngblood by John Oliver Killens.

If you read none of the other pieces of fiction that will be recommended here today, I implore you to read this one. I must admit that I nearly jumped for joy as I went through it nearly ten years ago. You will see why in a moment.

John Oliver Killens was born in Macon, Georgia, a rural part of the state, in 1916. He was politicized in the Southern Negro Youth Congress, an offshoot of the National Negro Congress I discussed above, in the 30s and 40s. He studied law at Howard University in Washington DC until the outbreak of World War II. He joined the army and went to war in the Pacific theatre. At the end of the war, he returned to Washington and went to work for the National Labor Relations Board and then the CIO. At the end of the 40s, he moved to New York City to become a novelist.

Youngblood was his first novel. Killens described his mood at the time as one of ‘militance and revolutionary impertinence’. The feeling is clearly expressed in this novel of Black resistance to white supremacy.

Youngblood is an extraordinarily rich multi-generational novel of a Black family, the Youngbloods, in rural Georgia. It takes place from around the first decade of the 20th century until just after the introduction of the NRA.

In lieu of a plot summary, I think it better to focus on the general theme of the book. And that theme consists of a call to fight the indignations and violence of white supremacy; not with words, and never with street protests, but with direct action and counter-violence when necessary. The Youngblood men and women, old and young, refuse to be treated as less than human by white people. The novel portrays the everyday micro-battles of Black people; it consists of each family member’s struggle against white employers who want to belittle them and rob them of the money they are owed, and of the various traps that are set to ensnare Black men into being lynched for having sex with white women.

The overarching message of the novel is: no compromise with white supremacy; no resignation, no reconciliation. There must be all out war against the evil. In this book, and his other novels, Killens anticipates Huey P. Newton’s philosophy of Revolutionary Suicide, which Newton describes as: ‘having such a strong desire to live with hope and human dignity that existence without them is impossible’. I do not want to give away the plot of the novel, and especially its final harrowing scenes, but it certainly embodies this idea.

Let me just give you a taste of the language and sentiment found throughout the novel. The speaker in this passage is the grandmother of Laura Lee, who becomes the wife of Joe Youngblood, the novel’s main male protagonist:

Honey, don’ choo never let em walk over you-don’ choo do it—Fight em, honey—Fight em every inch of the way, especially the big rich ones—like—like them Tuckers. They the one took over where ol’ marster left off. They lynch us, they starve us and they work us to death, and it ain-na gonna change till you young Negroes gits together and beat some sense in their heads. So fight em, sugar pie. Aah Lordy, honey.

Killens was a contemporary of James Baldwin. In fact, Baldwin’s first novel,Go Tell It On the Mountain, was published only a year before Youngblood. While I am certainly glad to see widespread renewed interest in Baldwin’s work, I have some worries as to why he has been elevated above the much more radical – and I must say stylistically accomplished – John Oliver Killens. While he excelled as a social psychologist, Baldwin had no discernible political commitments. In his novels, one gets the sense that he is trying to find paths of reconciliation between whites and Blacks in America. Killens wants this as well. But first, he seems to say, white supremacy in industry and law must go.That is the first and most important fight.

In short, and I have often been howled down for saying this, it is almost safer for white liberals to embrace James Baldwin because he doesn’t say anything that any of them – living in the early 21st century – could object to. The same cannot not be said about Killens. His militancy is absolute, uncompromising, and makes for discomfort.

Organising

I have spent so much time on resistance novels, I can only cover one novel under the organising category. I had originally planned to do Alexander Saxton’s The Great Midland (which I highly recommend) and Ruth McKenney’s Industrial Valley. The latter of these alone will have to suffice.

Ruth McKenney was born in Indiana and grew up in suburban Cleveland. Her insight as a journalist, her only connection to working-class life, was obtained through her father, who was a factory manager. Ruth McKenney was a member of the Communist Party. She joined the editorial board of The New Masses, the primary newspaper of the CPUSA, in 1937. Industrial Valley first appeared in 1939. The novel is mostly true to the events it covers. It is set in Akron, Ohio, which is in the heavily industrialised northeast part of the state. In the early 20th century, Akron was known for being the centre of the rubber industry in America.

Industrial Valley gives a gripping account of one city’s downward economic spiral after the 1929 crash. Working men put out of work, their wives struggling to feed their children, and the bosses scheming and plotting to take advantage of their desperation.

The novel also gives one of the best extended accounts we have of trade union organising after the passage of the NRA. In one especially good storyline, an organiser who has struggled for years to build unions on the shop floors of the different companies finds himself overwhelmed with workers who want to unionise after they get wind of the new law. So much so that he ends up going to Washington to appeal personally to the president of the AFL for help in organising.

None of this is portrayed in a simplistic or cartoonish way. McKenney does not gloss over the difficulties that unions face in sticking together and ringing concessions from the bosses. She is equally clear eyed about the class consciousness of the workers and their ability to keep their union leaders on a tight leash. There is no indication of workers being the victims of manipulation by professional organisers. They call the shots.

McKenney captures not only the mood and intentions of the workers, but their sense of ironic sensibility, as is displayed in one of my favourite passages:

“Ain’t it a shame,” a big pitworker drawled in his down-State Alabama speech. “The poor old Goodyear company is sure limping along these days with only five and a half millions to show for a whole year’s work. Fellows, we oughn’t to be so hard on the company, now that we know how they just pulled through last year by the skin of their teeth. No, sir, we ought to understand now why they got to have the eight-hour day and cut the rates”

And to those who still doubt the power of workers to recognize their own interests and respond to a common class enemy, McKenney set the record straight:

The CIO was an organic growth in Akron; it developed out of mass unemployment, bank failures, wage cuts, and speedup. John L. Lewis is a hero in Akron today [in 1939] not because he was a Man on a White Horse to workers—but because he supplied courageous leadership to the forward surge of the labor movement.

Argument

On to the representing argument category. By this, I refer to works of fiction that make a more direct critique of capitalism, or as was present in many books of the period, racial capitalism. Alice Childress’s book Like One of the Family delivers such critiques with wit, charm, and devastating intelligence.

Alice Childress was primarily a playwright. She started her theatrical career as an actress. From 1941 to 1949, she was a member of the American Negro Theatre, working alongside such rising talents as Sidney Poitier, Harry Belafonte, Ruby Dee, and Ossie Davis. In the 40s and 50s, she was involved in a number of left wing and communist political and theatrical groups, including the Committee for the Negro in the Arts (CNA). In this capacity, she fought for the rights of artists in the theatre industry, getting advances and guaranteed pay for off-Broadway theatrical union members.

Like One of the Family came out in 1956. It brought together a series of columns Childress had written for Paul Robeson’s Freedomways newspaper. In the book, Childress adopts the persona of Mildred, a Black domestic worker who lives and labours in New York City. The book is composed of a series of conversations between Mildred and her friend Marge. The vignettes are set up so that Marge never speaks, but silently hears out Mildred as she delivers sharp insights into race, class, the nature of domestic work, and what it means to be a Black woman in mid-20th century America.

One of the best features of this book is that it captures the Black American oral tradition and puts it in the service of high criticism. A few examples:

[Here Mildred is recalling to Marge a conversation she had with her white employer]

“…when you told me the other day that you’re going to drop by my house and see me sometime I don’t appreciate that because I never invited you, and you never had me to your house except to do a day’s work.” She looked down at her hands as I went on. “I don’t think it’s fair that you can invite yourself to my house and I can’t tell you that I’ll be over here for tea on Sunday afternoon.”

[Speaking directly to Marge]

Have you ever heard any of these politician speakers say “Jim Crow”? No, they will say the race situation or the problem of minorities or race tensions or somethin’ like that. You may think as hard as you might, but you’ll find nobody comes down to the nitty-gritty when it calls for namin’ things for what they are… You right, we always some “problem” and people takin’ potshots at us is always called “tension” and why you and me who have been citizens for generations should be called “minorities” is more than I can see.

And one final passage:

[Again, speaking directly to Marge]

That is why we need a union! Why shouldn’t we have set hours and set pay just like busdrivers and other folks, why shouldn’t we have vacation pay and things like that?... Well, I guess it would be awful hard to get houseworkers together on account of them all workin’ off separate-like in different homes, but it would sure be a big help and also keep you out of a lot of nasty arguments.

The erasure of radical literature

Enough. I hope you get the point by now. The writers I have selected were trying to represent working-class life. All of them had political commitments and all were involved in left-wing organisations. But that was a different time from our own. Back then – starting really in the 1930s – joining the Communist Party or a Popular Front organization such as the National Negro Congress was seen by many as being the only practical means for enacting social change. Authors with such political affiliations were not only targeted by the state but denigrated by mainstream literary critics and the Anti-Stalinist liberal left intelligentsia – critics and academics.

This is not the place or occasion to rehearse that sad and sordid history. It must suffice to say that recent scholars such as Barbara Foley, Michael Denning, Alan Wald, Lawrence Jackson, and Mary Helen Washington have done a great deal of work to renew interest in proletarian writing from mid-20th century America. This effort began in earnest more than 30 years ago. However, it is my belief that the stain of propagandizing for the Communist Party still sticks to the best of America’s radical authors. Their books go in and out of print (mostly out) because they are not taken seriously as literature. I don’t think any serious critic or English lecturer would actually say this today; but I suspect a sort of inertia has set in that keeps these books off of reading lists.

I feel obligated to say a few words more about this before moving on to practical applications to today’s political activists.

The authors I have reviewed were not interested in hortatory or formulaic writing. What they expressed was not propaganda but a view of the world. This is what all the best and most memorable literary artists do, and is why they continue to be read and celebrated. No one who has read D.H. Lawrence’s Women in Love, Kangaroo, and The Plumed Serpent can deny his clearly articulated Nietzschean ideology. Yet, the last I checked, he is still taught and his books are available to students and the public in a wide-range of inexpensive paperbacks.

Ayn Rand, who also wrote in the mid-20th century, repeatedly stated her intention of creating a new philosophy of capitalism and wrote two large books –The Fountainhead and Atlas Shrugged – that are stylistically well-executed. She makes greed a virtue, turns rapacious innovators into heroes, and ignores race completely. Her books have never been out of print, and she has gained a cult following among the American right.

In fact, we can take the matter back even further. When we do, the absurdity of making outcasts of authors because of their political beliefs becomes even more apparent.

Percy Bysshe Shelley’s Queen Mab and Laon and Cythna make plain the author’s commitment to socialism and his desire to advocate for it in his poetry. Yet he remains in the canon of English literature. (Despite repeated attempts to hang the de-politicized label of lyrical on Shelley’s poetry, their lyrical radicalism shines through). And if the expression of political conviction in fictional works disqualifies them from the category of literature, then we should clear the shelves of George Sand and Victor Hugo and cease reprinting Mary Shelley’s The Last Man and Leo Tolstoy’s Resurrection.

And what of our contemporary literary luminaries? What are we to make of Salman Rushdie, Barbara Kingsolver, Colson Whitehead, Pat Barker, and Olga Tokarczuk? Would any sane mind claim that they avoid making clear political statements in their books? If the answer is no, then why are they so lauded by critics and the larger reading public?

I don’t want to belabour the point. There is simply no basis for discarding literature written by people committed to a specific ideology. If a literary work consists of the distilled sensations of its author, then we should expect it to embody ideological perspectives and conceptions of all kinds when the author has strong views on the political, social, and economic order.

I must leave a few loose ends to get to my closing remarks. Perhaps I will be able to tighten some of them up during the discussion session.

Closing remarks

I want to stress the point, as I did in the last session, that I am not here to tell you as political activists how to do your job. You know how to do your job. My only aim is to give you a sense of the long political tradition you are part of, which may provoke some new ideas about how you practice. I think this way of doing political education, through history, also gives encouragement. It demonstrates that the battle has always been tough and seemingly insurmountable; but that we should not give up – the struggle is worth carrying on.

In this session, I have shown how words and language can be enlisted into the fight. All the authors I discussed were political activists before they became literary artists. This is something that any of you with growing creative impulses should take heed to. It is never too late to start putting your words into an art form that represents the struggles of your sisters and brothers in the labour movement. Now literature is the only artistic medium I am competent to discuss; but obviously, the same applies to any other art form you may be interested in.

I am a child of the 20th century. And thus, I am most comfortable with the printed word – and will most likely remain so for the rest of my days. But we have entered a different sensory world – one in which the printed word no longer dominates.

While writing novels, short stories, plays, and so forth is still worth doing, there is no reason to limit yourself to these forms. Although I still know little about them, I have been amazed at the few creations I have come across on podcasts and social media platforms such as YouTube and TikTok. At the moment, the reigning impulse on these platforms consists of self-indulgence. But there is no reason why the technology can’t be used to create art that represents worker-based causes throughout the nation and give voice to the people involved in them. This too is political activism. This too is doing something. This too is fighting for working people.

Recommended Reading

Daughter of Earth, Agnes Smedley

Youngblood, John Oliver Killens

Industrial Valley, Ruth Mckenney

Like One of the Family, Alice Childress

U.S.A., John Dos Passos

The Trexler Trilogy, Josephine Herbst

I Hear Men Talking and Other Stories, Meridel Le Sueur

Tell Me a Riddle & Yonnondio, Tillie Olsen

To Make My Bread, Grace Lumpkin

Daughter of the Hills, Myra Page

The Unpossessed, Tess Slesinger

Lonely Crusade, Chester Himes

The Great Midland, Alexander Saxton

Blood on the Forge, William Attaway

Uncle Tom’s Children, Richard Wright

Blacks, Gwendolyn Brooks

The Street, Ann Petry

The Grand Parade, Julian Mayfield

Trumbull Park, Frank London Brown

Christopher D. Reid is an independent researcher. He has an undergraduate degree in Political Science and graduate degrees in Human Relations and Philosophy. For the last ten years, he has studied the history of race, resistance, and political economy in the British and American Empires.

Comments ()