Since the 1970s, Britain has seen intense social struggles whose outcomes have reverberated around the world. Andy Ramsay surveys the legislative changes that paved the way for the repression experienced by unions and social movements today.

by Andy Ramsay

Part 1: Hostile Legislation, Police and Judiciary

Warren Zevon’s 1970s song ‘Send Lawyers, Guns and Money’ doesn’t really explain why they needed to be sent – only that the desperate narrator was ‘stuck between a rock and a hard place’ and that the ‘shit had hit the fan’. The quirky title, nevertheless, conveys a sense that some kind of serious conflict was anticipated. I used to think it odd (and funny, of course!) that lawyers were first on the list for the coming battle. Now that I understand how the law has been used – and continues to be used – against trade unions in the UK, I appreciate the prioritisation.

The 1970s were a bizarre time in Britain. Amidst all the hedonism and whimsy of Glam Rock, fashion disasters, Chopper bicycles, and excruciating Carry On films, the television would bring us flashes of the world outside the bubble. The war in Vietnam was ongoing. The struggle against the apartheid regime in Southern Africa continued. The Troubles were underway in the North of Ireland. In Chile, Allende’s democratically-elected socialist government was being overthrown in a bloody coup by Pinochet, backed by the West. The trade unions, engaged as they were in these struggles, connected the working class tangibly to that world outside. They were also a significant force in domestic struggles. The National Front were on the ascendancy. Racist and homophobic violence (including so-called ‘bashing’) was commonplace. Trade unions were at the forefront of the anti-fascist resistance.

There are no rose-tinted glasses here. British society of the time was blighted by violence, misogyny, racism and discrimination of all kinds – and trade union membership also reflected this. Nevertheless, the trade unions were popular and powerful. Can anyone nowadays imagine a trade union anthem reaching No. 2 in the UK Singles chart as ‘Part of the Union’ by The Strawbs did in 1973? Industrial militancy was everywhere – strikes, sit-ins, work-to-rules and go-slows. A novel form of industrial action, the work-in, was pioneered successfully by the Upper Clyde Shipbuilders Committee in Glasgow to stop shipyard closures. This action attracted world attention as well as considerable support from celebrities such as John Lennon. The unions effectively brought down Edward Heath’s Conservative government in 1974 when he chose to fight an election on a pledge to break them. However, what has largely been erased from the popular history of the time is how close the country came to a workers' revolution between 1972 and 1974.

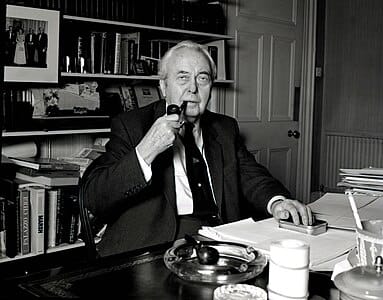

Not only had the government of the day lost control, but radicalised workplace militancy almost caused the state to collapse. Many of the unions had lost control of their members – or, put another way, the workers had freed themselves of the trade union leadership. Senior government, military and establishment figures reportedly met to plan a coup d’etat. In January 1974, while Edward Heath was still in power, the army occupied Heathrow Airport in a ‘Ring of Steel’ operation codenamed Operation Marmion. The reasons for the operation were never made clear and it has long been speculated that it was a rehearsal for a coup. The operation was repeated by the military three more times that year after Harold Wilson’s Labour government came to power. Again, the reasons were not explained. Neither was the government informed in advance. Wilson considered them to be demonstrations of power and coup-capability by the armed forces. Later in the 1970s, a senior Conservative politician, Airey Neave, was reported to have met an intelligence agent to discuss the assassination of Tony Benn, a prominent socialist in the Labour party and an advocate of workers' control. Neave was himself assassinated one week later by the Irish National Liberation Army (the military wing of the Irish Republican Socialist Party).

These were volatile times. Perhaps a state counter-attack (short of a coup) might have been expected. Perhaps a campaign could have been anticipated in which new laws would be passed to rein in the trade unions. Given that trade unions brought down both Conservative and Labour governments, perhaps it was predictable that the attacks would come from both parties when in power. Perhaps it could also have been foreseen, given this existential threat to the unions, that the union hierarchies might acquiesce and fail to mount an effective resistance. Regardless, it is incontrovertible that the trade unions of today have had most of their rights, influence and power expropriated (at least for now).

I joined the Association of Scientific, Technical and Managerial Staffs (ASTMS) in 1978. Later ASTMS became Manufacturing Science and Finance (MSF) through mergers. For those wondering why they have never heard of these unions – MSF would become part of Amicus which in turn would become part of Unite through mergers in 2001 and 2007 respectively. I became an MSF Representative, and was Secretary of the MSF Group at the London teaching hospital where I worked in the 80s and 90s. I was active in the Communist Party of Great Britain (CPGB) from 1987 until its demise in 1992 and supported the CPGB’s ‘Manifesto for New Times’. I recently returned to active trade unionism after a break of some 25 years and found the labour movement to be a hollowed-out shell. This article was researched and written in an attempt to understand what had happened. I am not an expert – there may be a few inaccuracies relating to differences in the law between Scotland, England, Wales and Northern Ireland. Maybe mistakes. But it will largely be true.

I went to lengths in the previous paragraph to emphasise how involved I was with the Labour Movement in London. I was shocked to learn that we were being cut to ribbons during the period I considered myself most active. I knew there were attacks – but I hadn’t noticed the way the attacks were building on each other, to leave us all but useless in the end. Trade unions have now been rendered legally incapable of functioning beyond the narrowly-defined role of negotiating wages and terms and conditions of employment. Was the campaign just too insidious? Was I so focused on defending the National Health Service against Thatcher that I didn’t notice? Did my union, or my party, alert me to what was going on, but I wasn’t paying attention? I doubt I will ever know.

In the mid-20th Century the term ‘lawfare’ – a portmanteau of ‘law’ and ‘warfare’ – started to gain currency. It is a term used to describe the exploitation of legal systems to achieve political or ideological objectives. It has also been described as ‘the resort to legal instruments, to the violence inherent in the law, to commit acts of political coercion’. There can be no doubt that trade unions have been subject to a decades-long campaign of ‘lawfare’ involving hostile legislation, quasi-legislation, police and judiciary, and espionage by the security services.

This article leads us through the lawfare campaign in three sections, with a fourth section summarising where the trade union movement currently stands. Each of the first three sections will describe events in chronological order. The first part will deal with the hostile legislation and its implementation through equally hostile police and judiciary. The second part will describe the increasingly important area of quasi-legislation in restricting trade union activities. The third will focus on trade unions being subject to surveillance and espionage by security services; it will particularly focus on recent changes to the laws which facilitate this. The final section will ask whether the UK trade union movement is now dead in the water, or whether it can still be rescued; if it can, what do we need to do?

Tables 1 to 6 list (in chronological order) selected reports, legislation, quasi-legislation and actions that may be considered part of the lawfare campaign. It can be seen from the Tables on legislation that some of the laws deal specifically with trade unions and industrial relations, while others are criminal or public order acts that impact upon conduct of all peaceful protest. Extended powers given to the intelligence services, police, courts and criminal prosecution system from 2021 and 2025, by both Conservative and Labour governments, not only curtail trade union action but also repress wider civil society through the criminalisation of peaceful protest. The most extreme of these, perhaps, is the current Labour government’s use of anti-terrorist legislation to criminalise peaceful protest.

Labour and Conservative Governments 1964–1979

The start of the campaign can be traced to the period of Harold Wilson’s Labour government of 1964–1970, beginning with the report of the Royal Commission on Trade Unions and Employers’ Associations or the ‘Donovan Report’ (1968) and the White Paper ‘In Place of Strife’ (1969). The Commission was set up in order to seek solutions to the industrial unrest that was prevalent in UK industries at the time. It was intended, and at first looked probable, that the Commission Report would support the Labour government’s desire to reduce the power of trade unions, establish legislative interventions in major industrial disputes, and support a governmental policy on prices and incomes. However, after conflict within the Commission, the Report finally recommended that collective bargaining should remain the basis of wage negotiation. When ‘In Place of Strife’ (a White Paper based on the Report) was presented by the government there was considerable opposition within the cabinet, and between the government and the Trade Union Congress (TUC). The White Paper never led to legislation but was highly influential later, in the 1974–76 Wilson government, when the Trade Union and Labour Relations Act (TULRA) was drafted.

The Industrial Relations Act 1971, during Edward Heath’s Conservative government (1970–74), disregarded much of the Donovan Report and was based on a Conservative policy paper entitled ‘A Fair Deal at Work’. It introduced the concept of unfair dismissal (as recommended by the Donovan Report) and its enforcement by a new National Industrial Relations Court (NIRC); however, overall worker protection was reduced in comparison to that proposed in the Donovan Report. Workers could belong to a registered trade union, an unregistered trade union or no union at all. Only registered trade unions had legal rights and immunities, but had to provide authorities with detailed procedures for decision-making within the union related to taking industrial action. Loopholes allowed insertion of ‘no strike clauses’ in workers contracts. Strikes without formal union authorisation (wildcat strikes) were restricted and limitations were placed on authorised strikes. The NIRC was empowered to settle disputes through injunctions. The Act was opposed by the Trades Union Congress (TUC). Following the arrest and imprisonment of the Pentonville Five (dockers who had defied an NIRC injunction) the TUC called for a General Strike – the threat of which led to their release. Heath called for a General Election and fought a campaign around breaking the trade unions – ‘Who Governs Britain?’. He lost.

The return of Harold Wilson as Prime Minister of a Labour Government (1974–76) led to the Trade Union and Labour Relations Act (TULRA) 1974. Through this the 1971 Act was repealed. Rights against unfair dismissal were retained and strengthened. The Health and Safety at Work Act (HSWA) 1974 was enacted and included a provision that workplace safety representatives were also trade union representatives. Union lay representatives and officials were granted rights such as paid time off work for training in industrial relations or Health and Safety. Between 1974 and 2007 the numbers of fatal and non-fatal injuries at work both fell by over 70%. However, much of TULRA was based on goodwill and voluntary constraint on the side of both unions and employers. Union recognition and collective bargaining agreements were not bound by force of law – leading to the famous Grunwick strike on trade union recognition (1976–78).

This two-year strike for trade union recognition by largely immigrant East African-Asian women at the Grunwick Film Processing Laboratories became a trade union cause celebre. It was characterised by police brutality and mass arrests of trade unionists. The TUC eventually withdrew support for the strike and the workers called it off. The strike leader, Jayaban Desai, went on hunger strike outside the TUC Headquarters in protest at their betrayal. The strikers' demands for trade union recognition were never met. Trade union immunities were not guaranteed. Agreed restrictions on unofficial strikes failed to stop them in some industries.

Together with the Employment Protection Act 1975 (EPA), the TULRA and the HSWA were the basis of the Social Contract, a pact between the Labour Government and the TUC intended to control wage inflation.

In return for the Acts above, alongside increased social expenditure and controls on the cost of living, the union leadership agreed to voluntary wage constraints in line with a government income policy. Coates and Topham describe ‘creative interpretations’ of the law ‘by judges who made it clear their non-acceptance of the general [trade union] immunity principle’. If the action failed to qualify in the judge’s opinion as a trade dispute, those taking action lost all immunity from the law. Secondary actions (actions by workers who are not involved in a trade dispute in support of workers who are) became especially vulnerable through judge-made law. Flying pickets (groups of striking workers that moved from one workplace to another in order to picket) were a particular target. The first-ever national building workers strike in Britain started in August 1972. It ended in the September with workers winning a substantial pay-rise. There then followed a vindictive campaign by the Heath government, the police and the judiciary, that was instigated by the National Federation of Building Trades Employers (and notably Robert McAlpine, who later became Treasurer of the Conservative Party). Pickets were charged with conspiracy and other offences. This led to convictions of 24 workers and heavy prison sentences. The convictions were only quashed in 2024 after a 15-year campaign. The government was shown to have interfered in the case.

New methods of mass policing also made it more difficult to picket effectively, as witnessed in the Grunwick strike of 1977. These included deployment of the Special Patrol Group (SPG) of the Metropolitan Police – a group with a reputation for deadly brutality and previously reserved for serious public disorder and terrorism threats. Moreover, the government legislated to make resistance to redundancies liable to criminal charges when, in the Criminal Law Act 1977, it made trespass a criminal offence. This was clearly intended to discourage factory occupations, which were becoming common as a way of combatting threats of plant closures.

Table 1: Labour and Conservative Governments 1964–1979

Dates, Prime Minister, Party |

Reports, White Papers, legislation or actions |

Useful links* |

Oct 1964 – Jun 1970 Harold Wilson Labour |

The Royal Commission on Trade Unions and Employers’ Associations or Donovan Report (1968) In Place of Strife (1969) |

Report of the Royal Commission on Trade Unions and Employers Association (Donovan) |

Jun 1970 – Mar 1974 Edward Heath Conservative |

Industrial Relations Act (1971) based on ‘A Fair Deal at Work’ (1968) |

|

Mar 1974 – Apr 1976 Harold Wilson Labour |

The Social Contract Trade Union and Labour Relations Act – TULRA (1974) Health and Safety at Work Act 1974 Employment and Protection Act (1975) |

Social Contract (Britain) - Wikipedia Trade Union and Labour Relations Act 1974 - Wikipedia Health and Safety at Work etc. Act 1974 - Wikipedia |

Apr 1976 – May 1979 James Callaghan Labour |

Criminal Law Act (1977) |

The Social Contract broke down, leading to widespread strikes in the so-called Winter of Discontent (1978–79) and ushering in a Conservative government under Margaret Thatcher. The back-to-back Conservative governments of Margaret Thatcher and John Major (1979–1997) brought in rafts of anti-trade union laws over the 18-year period.

Conservative Governments 1979–1997

The Employment Act 1980 was the first of the anti-trade union laws of Thatcher’s government. A key requirement of the act was that unions had to hold postal votes instead of in-person ballots. As well as making ballots more expensive and more complicated for the unions, this requirement also resulted in delays, allowing employers valuable time to prepare for industrial action. It also required ballots on the existence of ‘closed shops’ (union-member only workplaces) with support from 80% of workers in a particular industry to maintain them. Public funds were to be made available for expenses related to printing and posting ballots to encourage secret balloting.

The Act restricted lawful picketing to those attending at or near their own place of work. It also removed immunity from secondary action unless it was designed to put direct pressure on the employer in dispute by interfering with their business, with their suppliers, or their customers. This restriction on secondary action also covered the practice of ‘blacking’ (refusing to carry out work on particular products or for particular clients). One of the most famous and effective instances of blacking was by union members at the Rolls Royce factory in East Kilbride, Scotland, from 1974 to 1978. The factory serviced the engines from fighter jets, including those that the Chilean Air Force (CAF) used to support Pinochet’s coup. Trade unionists and socialists in Chile were being persecuted at the time. By refusing to work on CAF engines that had been sent for servicing, the East Kilbride workers left the CAF with no functional fighter planes at one point. This was legal at that time. Contrast this now with workers having no option (aside from quitting their job) but to work on materials being supplied to the Israeli military conducting a genocide. Or contrast with the consequences today of taking out military planes that are supporting a genocidal campaign in Gaza. Following Chile’s return to democracy, three of the East Kilbride workers were awarded the Order of Bernardo O’Higgins. It is the highest award that Chile can bestow upon foreigners.

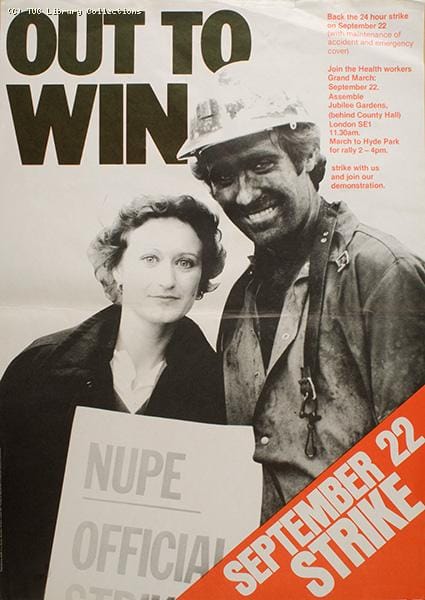

In the same year as the Employment Act, an act seemingly not related to industrial relations, the 1980 Social Security Act, had a major impact on the UK miners’ strike 4 years later. The 2nd Employment Act 1982 built upon the first by outlawing ‘closed shops’. It also more narrowly defined a ‘trade dispute’ as related to pay and working conditions only and restricting the circumstances in which industrial action could be taken. This included removing trade union immunity for secondary strike action, or ‘sympathy strikes’, except under certain conditions. In 1982, before the Act, firefighters and printing workers among others went on strike in support of nurses and NHS staff. Over 2.25 million workers in the UK took part in a national day of action in one way or another. Strikes closed over 65% of docks and 80% of mines. This example of union solidarity and collective pressure, the greatest since the General Strike of 1926, faltered in late 1982 as the Act approached Royal Assent.

Another highly significant component of this Act centres around the legal term ‘tort’. Tort is a civil wrong that occurs when one person or entity causes injury, harm or damage to another leading to legal liability. This can arise from intentional acts, negligence, or failure to act when there is a duty to do so. Tort law provides remedies for the injured party, typically in the form of damages. The 1982 Act removed trade unions’ immunity from actions in tort law, which had been in place since the 1906 Trade Disputes Act. This now allowed employers to seek injunctions against trade unions. They could also sue trade unions for damages, which in turn could lead to the sequestration of union assets. Damages awarded would be limited to a maximum of £250,000, but there were no limits to fines if injunctions were ignored and the union was found guilty of contempt of court.

The Trade Union Act 1984 gained Royal Assent three months after the start of the Miners’ Strike of 1984–85. It required unions to elect new General Secretaries every five years and to validate their funds every 10 years. It also made secret ballots a legal requirement for any strike to be legal. The National Union of Mineworkers (NUM) leadership had voted against a national ballot with Michael McGahey quoted as saying ‘we shall not be constitutionalised out of a strike… Area by area will decide and there will be a domino effect’. This allowed the legality of the miners’ strike to be questioned and caused a bitter dispute which split the NUM along regional lines and the formation of the Union of Democratic Mineworkers (UDM) in Nottinghamshire and Derbyshire. The term ‘union barons’ started to appear in the press, vilifying union leaders for taking advantage of their members for political purposes.

The 1980 Social Security Act mentioned earlier came into play against the miners. Strikers had never been eligible for welfare benefits, but their dependants had been able to receive benefits in previous disputes. Clause 6 of the 1980 Act banned dependants of strikers from claiming a benefit called ‘urgent needs payments’. Moreover, the Department of Health and Social Security increased pressure on the miners, as well as hardship, cold and hunger on their families, by making a compulsory deduction of £15 (worth £51.18 in 2025) from other benefits in lieu of a strike fund payment supposedly made by the NUM. This was based on payments earlier in the strike which were not paid in later months as funds had become exhausted.

Violent conflicts such as the Battle of Orgreave during the miners’ strike, as well as other conflicts such as the Battle of the Beanfield (with police deployed against New Age travellers at Stonehenge) were cited as justification for the Public Order Act 1986. This legislation created a number of new public order offences including: riot; violent disorder; fear or provocation of violence; intentional harassment, alarm or distress; and harassment, alarm and distress. It also imposed conditions upon processions and public assembly ‘to provide police with powers to prevent serious public disorder, serious criminal damage or serious disruption to the life of the community’. The original legislation defined a public assembly as ‘20 or more people in a public place which is wholly or partly open to the air’. A later Act by the New Labour government made this definition more draconian. With the UK’s most powerful union divided, and the miners defeated in 1985, legislation was then introduced to further reduce union power through the Employment Act 1988 and the 1990 changes to the Employment Act.

Harking back to the ‘union barons’ media refrain of the miners’ strike, the Conservative government claimed to further protect ‘moderate trade unionists’ by preventing workers who refused to strike from being punished by their trade union through, for example, expulsion or fines. The 1988 Act also gave union members the right to go to court and request a ‘restraining strike action’ in the absence of a proper strike ballot. It furthermore required separate pre-strike ballots at each place of work engaging in industrial action, and also introduced the first inkling of how quasi-legislation might also be used against trade unionists. The Act gave the Secretary of State the power to issue Codes of Practice (CoPs) related to trade union ballots and elections. As we will see later, these CoPs have become significant tools for the state. The 1990 Act doubled down on this by permitting employers to dismiss workers engaged in unofficial strike action, and trade union immunity was removed from those engaging in industrial action in support of an unofficial striker who had been dismissed. The Act also removed all remaining forms of secondary action still protected by law.

The post-Thatcher Conservative Government led by John Major continued the previous administration’s work. The 1992 Trade Unions and Labour Relations (Consolidation) Act required that a trade union must be recognised by an employer for the purposes of collective bargaining and that a trade union must be ‘recognised’ by the concerned employer to lawfully call for strike action. The 1993 Trade Union Reform and Employment Rights Act (TURERA) introduced considerable legislation related to the administration, financing, independent oversight, mergers, and political funds of trade unions. While repealing Government support for trade union ballots, it nonetheless required all trade unions to conduct fully-postal ballots for all industrial action, to provide a minimum of seven days’ notice to employers of their intention to ballot on industrial action, and to provide employers with sample ballot papers. Employers could request the names of all those being balloted. Ballots of more than 49 members needed formal independent oversight. Employers needed to be informed of ballot results and given at least seven days’ notice of industrial action.

The Act also allowed employers to take action which discriminates against trade union membership in order to bring about changes in negotiating arrangements – this could include offering higher pay to those workers giving up rights to collective bargaining. Employees had to provide employers with written consent every three years for trade union subscriptions to continue being deducted from wages. This Act also put the nail in the coffin of the Wage Councils. The Wage Council Act of 1945 had applied systems for sectoral minimum wages in specific industries. They had been gradually dismantled over decades, but TURERA abolished the last remaining 26 Wage Councils which protected around 2.5 million low-paid workers. There was now no union mechanisms for ensuring minimum wages.

The Criminal Justice and Public Order Act 1994 was described by Jeremy Gilbert (Professor of Cultural Studies, University of East Anglia) as a piece of legislation that was explicitly aimed at suppressing the activities of certain strands of alternative culture, the main targets being squatting, direct action, football fan culture, hunt sabotage and free parties (raves).

The Act included:

- Substantial changes to an accused person’s right of silence when cautioned by police – allowing adverse inferences to be drawn from the silence in certain circumstances.

- Greater rights for police to take and retain intimate samples.

- Increased police powers of unsupervised stop and search.

- The criminalisation of previously civil offences related to trespass and nuisance on land which would affect many forms of protest including hunt sabotage and anti-road protestors.

Table 2: Conservative Governments 1979–1997

Dates, Prime Minister, Party |

Reports, White Papers, legislation or actions |

Useful links* |

May 1979 – Nov 1990 Margaret Thatcher Conservative |

Employment Act (1980) Social Security Act (1980) Second Employment Act (1982) Trade Union Act (1984) Public Order Act (1986) Employment Act (1988) Changes to the Employment Act (1990) |

Employment Act 1980 - Wikipedia The 1980 Social Security Legislation: The Great Welfare State Chainsaw Massacre? on JSTOR Employment Act 1982 - Wikipedia Trade Union Act 1984 - Wikipedia Public Order Act 1986 - Wikipedia Employment Act 1988 | LexisNexis Employment Act 1990 - Wikipedia |

Nov 1990 – May 1997 John Major Conservative |

Trade Union and Labour Relations (Consolidation) Act (1992) Trade Union Reform and Employment Rights Act (1993) Criminal Justice and Public Order Act 1994 |

Trade Union and Labour Relations (Consolidation) Act 1992 - Wikipedia Trade Union Reform and Employment Rights Act 1993 - Wikipedia |

The New Labour Governments 1997–2010

Following the election of a New Labour government headed by Tony Blair, with John Prescott (a former National Union of Seamen official) as a Deputy Prime Minister, many in the labour movement expected wide repeals of the anti-trade union legislation of the past 18 years. However, they had failed to take account of the shift in Labour Party values in the lead-up to the election. At its 1995 conference the party voted to amend Clause IV of its constitution. This included the removal of a commitment to ‘the common ownership of the means of production, distribution and exchange’. Dropping this socialist commitment was followed in 1996 by a new manifesto ‘New Labour, New Life for Britain’. This reform of the party was intended to make it more appealing to ‘Middle England’ and was responsible for its subsequent electoral successes.

There was no broad repeal of anti-trade union laws by the New Labour government, although there were some gains for workers. The Deregulation (Deduction from Pay of Union Subscriptions) Order 1998 removed the requirement for employees to ‘check off’ their subs payments every three years. The National Minimum Wage Act 1998 required employers across the UK to pay a minimum wage to most types of workers. The minimum wage was originally defined in two age groups: 18–21 years and 22 years or over. The policy had long been controversial in the Labour Party, with some members believing that in practice the national minimum wage would become close to a maximum wage as employers would be content to pay slightly above and claim that they paid higher than the National Minimum Wage. Some in the Labour Party also felt that it would undermine the need for collective bargaining and the need for trade union membership.

The Employment Relations Act 1999 brought in legislation that allowed for three months unpaid parental leave and up to 18 weeks paid maternity leave after 1 year of service. It amended the law on ballots for industrial action so that, for example, unions did not need to provide employers with the names of those balloted. There was legislation to prohibit the blacklisting of trade unionists by employers. Statutory procedures were brought in for union recognition in businesses with more than 20 workers where the majority of employees wanted it. The right to be accompanied by a companion during disciplinary or grievance procedures was established. The companion may be a lay or employed trade union official who the union has certified as having the experience or training for such a role. The Act also gave those undertaking lawful industrial action protection against unfair dismissal for the first eight weeks of a strike. Largely, however, the Conservatives’ anti-trade union legislation was left intact.

The New Labour Government brought in anti-terrorist legislation in 2000 that would have seemed to have no bearing at all on trade union activity or on the rights of peaceful protestors. However, the Terrorism Act 2000 would later be weaponised by Keir Starmer’s Labour Government to criminalise peaceful protestors in 2025. The use of this Act is covered later in the text.

In The Conduct of Employment Agencies and Employment Businesses Regulations 2003 the legislation prohibited employment agencies from supplying agency workers to replace workers taking part in official industrial action. A piece of public order legislation, however, made the Conservatives’ Public Order Act 1986 even more draconian with a revised definition of ‘assembly’. The Anti-Social Behaviour Act 2003 reduced the minimum number of people in an assembly to two and removed the requirement for it to be open to the air.

Some very limited legislative changes were included in the Employment Relations Act 2004. With regards to protection of workers undertaking a lawful strike, the protection against unfair dismissal was extended from eight to 12 weeks. It was also stipulated that days of ‘lockout’ where employers prevent employees from working should not count towards the protection period. Amendments provided for the setting up of a Trade Union Modernisation Fund and to tackle unfair or intimidatory practices in trade union ballots. A further amendment allowed for expulsion of racist or extremist members from trade unions.

The Employment Act 2008 was an amending statute that sought to remedy some perceived problems related to the application of the laws in respect to resolution of industrial disputes, the enforcement of minimum wages and employment agencies standards. It is most remarkable for its amendment of trade union membership law in line with a decision by the European Court of Human Rights (ECHR) in the case of ASLEF vs UK. A member of the Associated Society of Locomotive Engineers and Firemen (ASLEF) had been expelled from the union on account of him being a member of the far-right British National Party (BNP). He successfully contested his expulsion at an Employment Tribunal under Section 174 of the 1992 Trade Unions and Labour Relations (Consolidation) which prohibits unions from excluding or expelling persons wholly or to any extent on the ground that the individual is or was a member of a political party. ASLEF eventually took the case to the ECHR which ruled in favour of ASLEF essentially that just as freedom of association made a worker free to join or not join a union, so is a trade union equally free to choose its members. The member was expelled. While few trade unionists will have sympathy for a member of a racist, quasi-fascist party, the case sets a precedent and allows the expulsion of members on the basis of political party membership. It is not inconceivable that, in future, some trade unions would wish to expel members of left-wing parties and this case would pave the way.

The Employment Relations Act 1999 (Blacklisting) Regulations 2010 expressly prohibited the compilation, use, sale or supply of trade union blacklists. The 1999 Act had provided allowance for the Secretary of State to make such regulations in regard to blacklists.

Table 3: Labour Governments 1997–2010

Dates, Prime Minister, Party |

Reports, White Papers, legislation or actions |

Useful links |

May 1997 – Jun 2007 Tony Blair Labour |

Deregulation (Deduction from Pay of Union Subscriptions) Order 1998 National Minimum Wage Act 1998 Terrorism Act 2000 Conduct of Employment Agencies and Employment Businesses Regulations (2003) Anti-Social Behaviour Act 2003 Employment Relations Act 2004. |

The Deregulation (Deduction from Pay of Union Subscriptions) Order 1998 National Minimum Wage Act 1998 - Wikipedia Terrorism Act 2000 - Wikipedia The Conduct of Employment Agencies and Employment Businesses Regulations 2003 Anti-social Behaviour Act 2003 - Wikipedia |

Jun 2007 – May 2010 Gordon Brown Labour |

Employment Act 2008 Employment Relations Act 1999 (Blacklisting) Regulations 2010 |

Employment Act 2008 - Wikipedia Employment Relations Act 1999 (Blacklists) Regulations 2010 - Wikipedia |

Conservative Governments 2010–2024

The Conservative-Liberal Coalition Government of David Cameron and Nick Clegg (May 2010–May 2015) was associated with no particular anti-trade union legislation and it is tempting to assume that Liberal values held it in check. The examination of the passage of the Trade Union Bill 2015–16, which became the Trade Union Act (2016), reveals its first reading was in July 2015, some two months after the coalition government was dissolved and the Conservatives resumed control.

The Trade Union Act of May 2016 was perhaps one of the most restrictive Acts to that date. The notice period that unions were required to give employers of strike action was doubled to two weeks and a package of rules were introduced regarding the validity of strike ballots. It introduced a new requirement for a minimum 50% turnout of eligible union members voting if a ballot was to be valid. In most cases, a 50% turnout with more than 25% voting ‘yes’ would be a valid ballot in favour of a strike. However for workers in certain services that were considered essential (including health, school education and transport) the law required that at least 40% of those entitled to vote had to support strike action for it to be legal. The conduct of legal strikes was also the subject of legislation. A Union Supervisor carrying identification and a letter of approval from the union was now required on each picket line.

Boris Johnson’s government of 2019–2022 produced two Acts that impact upon trade union activities. The first was the Police, Crime, Sentencing and Courts Act (2022) which made it a statutory offence to ‘intentionally or recklessly cause a public nuisance’. Actions that amounted to this were loosely defined – ‘causing serious distress, serious annoyance, serious inconvenience or serious loss of amenity’ – but, potentially, all were serious crimes. Furthermore, the charge of ‘conspiracy to intentionally cause a public nuisance’ made even planning a potentially disruptive action a serious crime that carried potential imprisonment.

The second Act of relevance was the Repeal of the Conduct of Employment Agencies and Employment Business Regulations Act (2022). This Act repealed Regulation 7 of the 2003 Act, thus allowing agency workers once again to be used for replacing workers involved in strike action. Thirteen trade unions sued the government in the High Court on the grounds that Kwasi Kwarteng, the Secretary of State for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy had not adequately consulted them, as was his duty under Section 12(2) of the Employment Agencies Act 1973. The unions won the case and the regulations were revoked with effect from August 2023, meaning agency workers could not be used to replace workers striking legally.

In 2022, the cap on damages for non-compliance with laws around strike action was raised to £1 million through the Liability of Trade Unions in Proceedings in Tort (Increases of Limits on Damages) Order 2022.

Liz Truss’s very short-lived term as Prime Minister produced no legislation of relevance. However, Rishi Sunak’s premiership of 22 months delivered two Acts of significance. The first was the Strikes (Minimal Service Levels) Act (2023) which forced trade unions to provide a minimum service level during a strike in health services, education services, fire and rescue, transport, border security and nuclear decommissioning. It allows employers to issue a ‘work notice’ stipulating who would work during a strike, with no guaranteed protection from unfair dismissal for those who refuse. What constitutes a minimal service is not defined but left to the discretion of the relevant Minister. Unions not providing minimum service levels during a strike lose immunity from being sued in tort for damages, and union members lose immunity from unfair dismissal. The Labour Party had stated that it would repeal the legislation if it came to power.

The second Act of relevance was the Public Order Act (2023) which expanded the powers of the police in the management of protests. New criminal offences were created that included ‘locking on’ to objects. To make matters worse, the right of protestors to claim they had lawful excuse for their actions (e.g., preventing the destruction of the planet) has been blocked by judges in the vast majority of protest cases (with the support of higher courts). It has been ruled by the Court of Appeal that a defendant’s ‘beliefs and motivation’ are too remote to be lawful excuse for damaging property. The only question in most trials of protestors is whether the defendants did what they are accused of; the justification behind any action is not relevant. Climate activists such as Just Stop Oil have been particularly hard hit by the legislation and interpretation of the law by the judiciary.

Table 4: Conservative Governments 2010–2024

Dates, Prime Minister, Party |

Reports, White Papers, legislation or actions |

Useful links |

May 2010 – Jul 2016 David Cameron Conservative |

Trade Union Act (2016) |

|

Jul 2016 – Jul 2019 Theresa May Conservative |

- |

|

Jul 2019 – Sep 2022 Boris Johnson Conservative |

Covert Human Intelligence Sources (Criminal Conduct) Act 2021 Police, Crime, Sentencing and Courts Act (2022) Repeal of the Conduct of Employment Agencies and Employment Business Regulations Act (2022) The Liability of Trade Unions in Proceedings in Tort (Increases of Limits on Damages) Order 2022 |

Covert Human Intelligence Sources (Criminal Conduct) Act 2021 - Wikipedia Police, Crime, Sentencing and Courts Act 2022 - Wikipedia Conduct of Employment Agencies and Employment Businesses (Amendment) Regulations 2022 - Wikipedia The Liability of Trade Unions in Proceedings in Tort (Increase of Limits on Damages) Order 2022 |

Sep 2022 – Oct 2022 Liz Truss Conservative |

- |

- |

Oct 2022 – Jul 2024 Rishi Sunak Conservative |

Strikes (Minimal Service Levels) Act (2023). Public Order Act (2023) |

Strikes (Minimum Service Levels) Act 2023 - Wikipedia Public Order Act 2023 - Wikipedia Public Order Act: New Protest Offences & 'Serious Disruption' - Liberty Public Order Bill: What you might not know about the anti-protest bill |

Labour Government 2024–Present

The current Labour Government of Keir Starmer came to power in July 2024 promising to repeal the Strikes (Minimum Service Levels) Act 2023. The Employment Rights Bill 2024 received its third reading in the Commons on 12 March 2025. It has now completed its second reading in the Lords and is at the Report Stage. There are considerable concerns among trade unions that the final legislation will be watered down. Already, the Labour Government is considering the introduction of fees that workers would need to pay make a claim at an Employment Tribunal. Such a change would impact hardest on low-paid workers.

A significant development during the tenure of this Labour Government has been the demonstrated ability of an over-stretched Crown Prosecution Service (CPS) in England and Wales to nonetheless respond rapidly and severely to civil disorder. The CPS claims independence from government influence except in circumstances where national security is threatened. The CPS response to the appalling racist, anti-immigrant riots that occurred in England following the tragic murders of three little girls in Southport demonstrated the capability, whether this response was influenced by government or not.

According to the CPS, three participants had been jailed within eight days of the first riots in Southport. In Plymouth, the first offenders dealt with by the courts were charged, convicted and jailed within 72 hours. As well as the expedited response by the CPS, the sentencing was also noteworthy. The severity of some of the sentences handed down were considered excessive by some and remain controversial. It was quite clear that the very rapid prosecution and lengthy imprisonment was part of a political response to the disorder. While trade unionists and most of the public will have little sympathy for racist, far-right thugs, any mechanism used against them in the current circumstances could be used against others now that the precedent has been set.

The Director of Public Prosecutions has stated that there is a strong public interest in prosecuting those who cause unrest at pro-Palestine protests. Protests have ignited strong public interest and public debate about the role of prosecutors and police in upholding law and order on our streets and in our communities. Indeed, mass arrests of protestors supporting Palestine Action have occurred since the statements, with over 530 protestors arrested on 9th August and 857 arrested on 6th September 2025. Many hundreds of other peaceful Palestine Action protestors around the country have also been arrested. This mass civil disobedience campaign against the proscription of Palestine Action as a terrorist group has rattled an increasingly authoritarian government and led to it pushing for increased police powers to ban repeated protests.

Table 5: Labour Government 2024–Present

Dates, Prime Minister, Party |

Reports, White Papers, legislation or actions |

Useful links |

Jul 2024 – present Keir Starmer Labour |

Employment Rights Bill introduced - would repeals Strikes (MSL) Act (2023). Crown Prosecution Service and expedited prosecution in civil disorder The Attorney-General for England and Wales can influence the conduct of prosecutions when national security is an issue. |

Employment Rights Bill - Parliamentary Bills - UK Parliament All justice is best served swiftly | The Crown Prosecution Service |

This completes a history of lawfare against trade unions and other civil society groups since the late 1960s. Part 2 will consider hostile quasi-legislation through codes of practice and guidance, as well as espionage and surveillance by security services.

Part 2 is available here.

Andy Ramsay is Scotland Area Organiser for the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW).

This article will also be published in the IWW's Wobbly Times newspaper.

If you would like to contact Andy or the IWW in Scotland you can do so at the following email address: scotland@iww.org.uk

Where a Wikipedia source is referenced, it is provided as a rough guide. We encourage readers to follow the links and carry out their own further research.

Comments ()