Just as the bogeyman of colonial India – the Thug – was both racialised and criminalised, so too have Black Lives Matter activists and those mobilised by the far-right, been drawn in to false equivalence by elite politicians.

By Sam Button & Panos Theodoropoulos

The summer just past saw Islamophobic riots spread like wildfire across the UK, the flames fanned through Facebook by Farage, Yaxley-Lennon and cronies. One of the most volatile far-right mobilizations in the UK was put down in short order by equally rapid community anti-racist organising. Starmer was quick to describe the rioters as 'thugs' and credit his law and order approach to the quelling of the rioting through police suppression.

This was not new, nor was the patronising rhetoric deployed by Westminster politicians. Indeed, the term ‘thug’ is readily deployed in the Anglosphere whenever elite groups seek to delegitimise social movements that go against their hegemony. And, while thug has also been reclaimed in various moments as a statement of power – most memorably through hip-hop's ‘Thug Life’ slogan – the phantasm of the Thug is nevertheless consistently used by elites to insinuate a figure that does not deserve to make claims about the societies in which they are denizens. The ‘marginalised’ or ‘oppressed’ are words that conjure up public sympathy; the Thug, on the other hand, deserves the repression that is directed at him (and, of course, the thug is usually scripted as masculine).*

The last time we saw a similar deployment of this term was when Boris Johnson condemned Black Lives Matter protesters as ‘thugs’ after they threw a statue of slave trader Edward Colston in Bristol docks. Indeed, the term has a long colonial history, a history that reveals how the British state polices and monopolises violence. Without harbouring an iota of sympathy for the far-right, we must remain vigilant as to how these terms hide wider meanings of repression – and of how easily that repression can be turned upon progressive social movements.

A brief history of the word ‘thug’

Thug comes from Thuggee, groups of armed robbers who were said to roam the Indian subcontinent during the long period of British colonialism in India. These groups of itinerant soldiers would wander from place to place, robbing and murdering travelers on roads and highways, offering their victims as human sacrifices to the Goddess Kali. Part-highwaymen, part-death cult, they were a group to be feared by colonisers and suppressed by the British colonial state.

They probably didn’t exist.

Modern scholarship on the subject of Thuggee suggests that they were an invention of British colonialists.

‘There is no doubt that thuggee – the system of deceit, robbery and murder practised by the thugs, held responsible by the British for over a million murders in India in the late seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries – inspired one of the strongest and most long-lasting orientalist discourses ever invented’, writes Alexander Mcfie.

The cultural influence of the Thuggee myth has been incredibly enduring, most notably in Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom, the archetypal white saviour working hand-in-hand with the British colonisers at the denouement of the film. Mcfie questions the veracity of the concept, identifying an archive single-handedly compiled by a William Sleeman, a British East India Company official, that was

‘itself an orientalist construction – that is to say, the product of a deep-seated European inclination to make an ontological and epistemological distinction between the Occident (Europe, the West) and the Orient (the East), which leads Europeans (Westerners) to characterise the Oriental as mysterious, backward, degenerate, irrational and inferior’.

Further to this, Professor S. Shankar skeptically writes that Sleeman both ‘discovered’ and ‘suppressed’ the Thuggee, and this was done in a particular way as to advance Sleeman’s career. Shankar continues:

‘Sleeman’s discursive invention of the Thuggee was taken up […] because it meshed well with emerging ideas regarding the shape of the state of colonial India [and] permitted the argument that this state should be a colonial law-and-order state, a state that saw its primary activity as that of restraining a criminal and violent population’.

Sound familiar?

The modern Thug

Both The Tory and Labour parties have historically described themselves as the parties of law and order. This was exemplified by the former Home Secretary Priti Patel, who once supported the death penalty, and echoed Johnson’s words when she described BLM protestors as ‘thugs and criminals’ in response to the global protests over George Floyd's death in 2020. Remembering the UK during COVID, we saw an unprecedented level of policing, the expansive governing of the most intimate aspects of how we live, many of which were not evidenced-based, but nevertheless remain on the statute books, and the demonisation of the public as irresponsible ‘Covidiots’. More than this, was the typical characterisation of communities of colour as violent and lawless which, in turn, leads to a justification of policies that are ‘tough on crime’.

Modern policing has its origins in colonial rule in India and Ireland. The Black and Tans were deployed to the so-called British Mandate of Palestine. Policing in the UK as we know it today would not exist without colonialism. And, as we have written previously, policing in the US is directly traceable to the recapturing of escaped slaves. Contemporary policing has emerged in tandem with colonial exploitation and the internal oppression of minorities. In this process, depicting these populations as somehow essentially inferior, violent, and deserving of repression was crucial to legitimise their violent control. ‘Thug’ is part of this wider history.

These tactics were recently extended to include majority white, working-class communities, who were justifiably outraged at violent murders. The far-right harnessed this anger, perverting it to suit their Islamophobic goals while of course exploiting latent racist narratives that have been allowed to fester in British society. They whipped up crowds through misinformation facilitated by social media, despite the fact that the autistic child who is suspected of the murder was a Christian choirboy. The fact that the stabbings happened at a Taylor Swift-themed yoga class, an icon of white femininity, made the deployment of racist disinformation, as the accused is Black, all the easier.

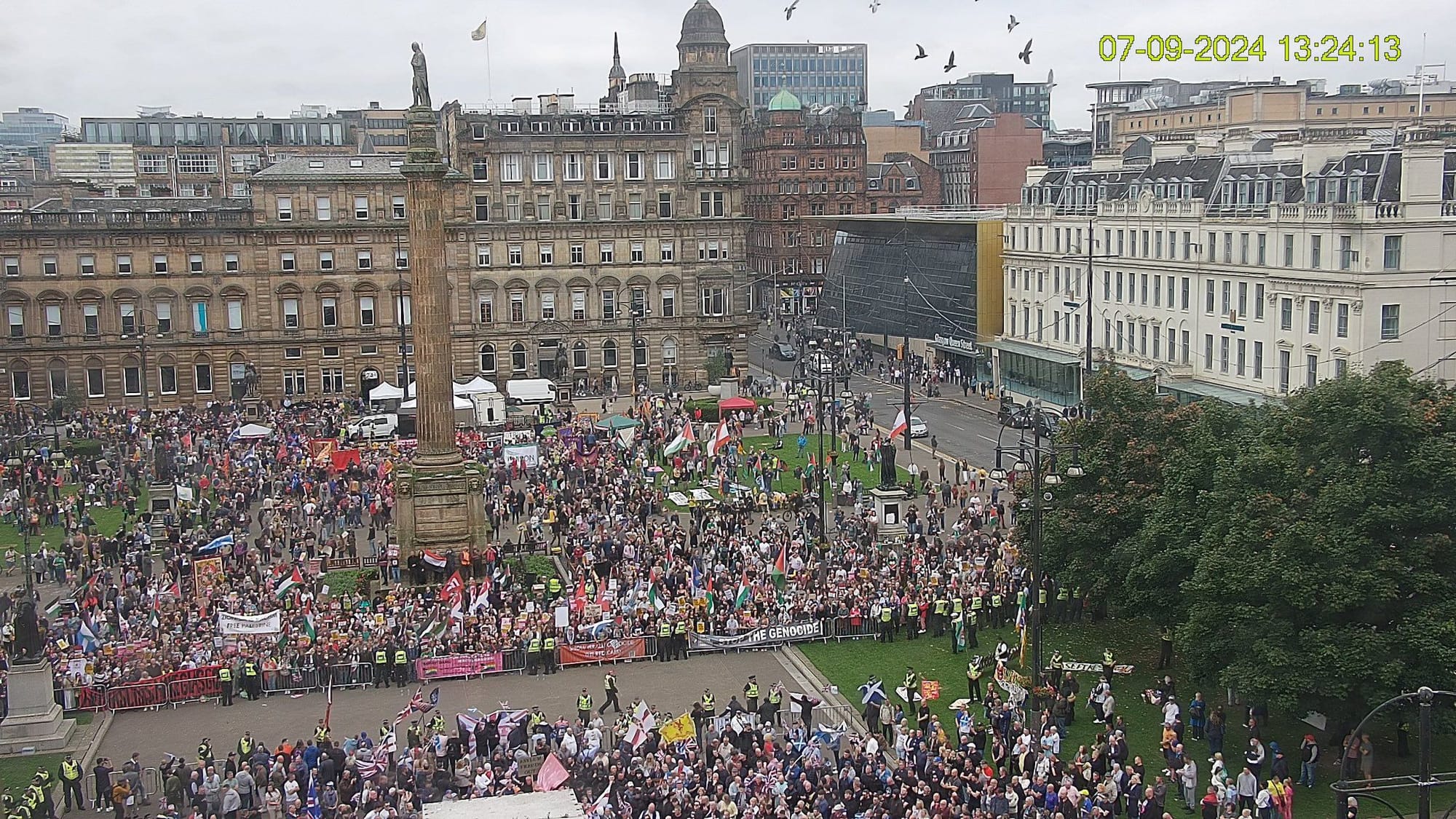

The image of white women under threat from the Black aggressor is a historically racist cultural deployment. These deployments took hold in some of the most deprived areas of the UK; the shell of post-austerity Britain is empty for the slithering insects of Farage and Yaxley-Lennon to make their home. Nevertheless, Yaxley-Lennon prefers escargot. However, the wider communities themselves were having none of it. In Glasgow earlier this month, anti-racist demonstrators outnumbered the far-right by five to one, a victory that was repeated across the UK.

Nothing is finished. Despite the success with which communities responded to the far-right threat, the re-invocation of thuggery as a way to describe oppositional action is a cause for concern. Thuggery is steeped in colonialist history. Just as the bogeyman of colonial India – the Thug – was both racialised and criminalised, so too have been Black Lives Matter activists and those mobilised by the far-right, drawn in to false equivalence by elite politicians.

These developments reflect and illustrate the authoritarian turn that Labour is fully invested in; they indicate the response that will be directed towards left-wing and anarchist action, should it emerge in the near future. For example, Hamza Yousaf called on the army to be released in the streets in response to the latest riots; this is a qualitative hardening of the level of legitimate repression in society. Similarly to calls against abortion in the United States, the more the unsayable becomes normalised, the nearer the reality it envisions. The depiction of these protesters as Thugs further legitimises state violence against protest; and this legitimacy will now be a part of the ruling class's arsenal, its deployment rendered more palatable by its association with anti-racism. In short, the use of the word Thug is not isolated; it is accompanied by a myriad of other meanings and suggestions, none of which push us towards an emancipatory, egalitarian future.

Instead of these approaches, we must look towards building community institutions, and focus on community education. As the anti-racist mobilisations demonstrated, we are much stronger than the State; Starmer will not protect us. We will protect ourselves. And, perhaps, in the process, we can shed some of the authoritarianism that we have been imbued with through our cultural upbringing.

*The participation of women in the riots by no means reduces the association of thuggery with a form of masculinity. If anything, it enforces it. These women are presented as outside the legitimate boundaries of femininity; by being presented as engaging in thug-like activity, they are used to re-establish the boundaries between proper femininity and its opposite. As always, these acrobatics re-establish white working class masculinity as dangerous and abject and re-confirm the notion that it is the working class, in general, that should either work or shut up (or, preferably, both).

Sam Button is a member of the Interregnum collective

Panos Theodoropoulos is a sociologist and a member of the Interregnum collective. He currently teaches at King's College London.

Comments ()