Despite increasing awareness of societal inequalities and the stigma that cultural and economic forces project onto our bodies, fatness still invokes a disgust response from a vast majority.

By Cat Lawton-Westerland

Fat liberation is a social movement that seeks to improve the lives of fat people by advocating for equal access to transportation and employment, as well as improving societal, personal, and medical attitudes towards fat people. This is often centred around myth-busting and educating to combat prevalent fat-phobic and dehumanising representations.

For many, fat liberation is seen as a kind of final frontier in the fight for equality.

Fatness is present in many social hierarchies and certainly remains relevant to gender equality and trans rights, classism and racism, body politics including healthism, ableism, ageism, and reproductive freedom.

Although the social issues facing fat people are normalised and minimised, fatness plays a role in every social interaction and colours the way fat people are viewed by individuals and institutions.

Trans people seeking gender affirming surgery are told they need to lose weight to be considered for the operation, despite weight having no impact on the procedure itself.

Fat mothers are deemed unfit to care for children and fat children are seen as abused and taken away from their families despite healthy, loving relationships. Fat parents are denied opportunities to foster or adopt children needing families, as well as not considered fit to receive in vitrofertilisation and other fertility treatments if their Body Mass Index is in the obese category.

The NHS still uses the outdated and unscientific measure (BMI) to judge a person’s fitness for treatment, and much of the equipment is designed for smaller bodies. This means that fat patients often have to wait longer to have access to the limited facilities that can accommodate them.

Stereotypes around fatness are also tied to classist and racist assumptions about unhealthy lifestyles and addiction. Often, foods from cultures outside of western Europe tend to be portrayed as primitive and low in nutrition. Additionally, there is an ignorance of the reality of people working multiple jobs and having less time to spend on reproducing our cultural expectations around perfect health. Regardless of physical activity and the demands of physical labour, poverty and fatness is equated with laziness.

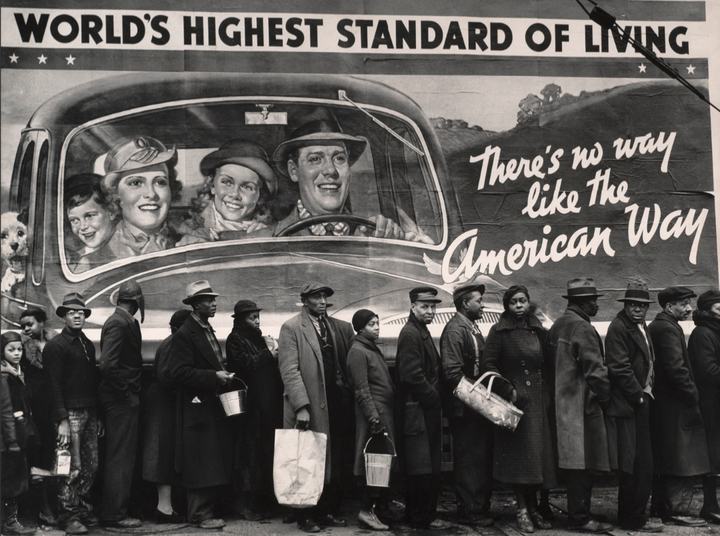

Capitalism’s reliance on individualism sees social positions and hierarchies as inherent or the result of behaviours, or as manifestations of individual flaws. We know that you can’t look at someone and see whether they’re kind or cruel, interesting or boring, creative or skilled. However, when it comes to fatness, our cultural script relegates fat people to lazy idiots or selfish, gluttonous shut-ins.

Despite increasing awareness of societal inequalities and the stigma that cultural and economic forces project onto our bodies, fatness still invokes a disgust response from a vast majority.

I recently attended a free conference in the University of Sheffield. The Fat Across Time (FAT) conference, organised by Gemma Gibson and Carlie Pendleton, was my first in-person experience of a space which existed for self-identified fat people, scholars of fatness, fat liberation allies, fat activists, and fat friends.

Although some attendees were chubby, average, or thin bodied people, this did not change the clearly fat-accepting attitude that characterised the event.

The space itself was curated to enable fat people to gather without the need to apologise for or justify their own existence. The act of taking this personhood and respect for granted is a foundational tenet upon which fat solidarity can flourish.

Personally, I have not identified as fat for long. Although the Instagram-centred body positive movement of the last ten years or so introduced me to the idea that I may not be totally unlovable and ugly and lazy and disgusting, I remained uncomfortable with my weight and filled with shame that I still carry and maybe always will.

It’s a very lonely thing to be a fat person trying to figure out how ashamed of yourself you ought to be, or how many times to keep trying to lose weight.

The reality is that diets only help people lose weight around 15% of the time in the long-term. We’ve known since the 1950s that diets and food restriction don’t work, and that most people regain the weight that they’ve lost, sometimes even gaining back more weight than they’ve lost.

Although people’s health outcomes are tied to living conditions and access to resources far more than personal conviction or effort, this hasn’t stopped the health and wellness industry from trying to convince you that all it takes is ‘one weird trick’ to suddenly have control over your body, and your life.

It doesn’t matter that these messages come most often from those who stand to gain your attention, time, and ultimately your money in exchange for the promise of your happiness. Or that your ‘health’ often translates to your productivity and ability to contribute your labour to the never-ending project of profit augmentation.

In this way, fatness, aging, pregnancy, poverty, and disability are no different from laziness as far as productivity is concerned. Your improved health is your own individual responsibility, and your deviation from the ‘perfect’ body is the result of individual faults rather than natural variation, and to do anything ‘well’ is to do it productively.

For most people it’s taken for granted that in a ‘natural’ society there would be no fat people (ignoring many indigenous and existing societies which live more closely in line with our imagined past, all of which include body diversity and variation in retained fat).

In most sci-fi or utopian futures, we imagine that there are no fat people because we have solved our societal shortcomings. In other words, the existence of fat people is an inconvenience that we will overcome, either because we will have ‘weeded out’ the lazy few through social control or because we will have perfected ‘health’ entirely.

The perfect citizen or worker is imagined as being young, white, heterosexual, cisgender, able-bodied, and male. This future population would need women only for their domestic and emotional labour which enables their male counterparts to be as productive as possible, hence the need for the nuclear family. Far from a perfect future, this is a dystopian reflection of our recent past.

Eliminating fatness and, by extension, disability from society (they are inextricable in many ways) is indeed a sinister project and echoes the eugenicist desire for a ‘perfect’ race.

Humans have always needed cooperation, diversity, and variety in the population to survive successfully. Trying to limit and control natural variants for the sake of purity and perfection undermines the humanity of those who do not fit into these limitations, and therefore leads to harm becoming more acceptable, or less objectionable, when enacted upon those bodies deemed ‘deviant’.

The topics discussed at the conference ranged from fat movement and exercise groups, treatment of fat patients by health professionals, fat representation, fat communities, and fat gender expression.

The speakers and attendees were a mixture of well-read academics, professionals and laypeople with a passing interest in new ideas about fatness. I found myself sitting next to a mother of two who worked in care, a postgraduate physicist, and the leader of a local dance class.

Upon entering I felt completely at home, I felt more likeable, and I was confident that I would be judged on my contributions more than my appearance. The novelty of this feeling is fairly tragic, but I cannot say how much it meant to be able to relax in a way that I had not felt able to as far back as I can remember.

Some of the barriers to solidarity between fat people are internal: people don’t feel comfortable identifying as fat, while others believe that they are only temporarily fat. You can’t advocate for better treatment if your problem is personal and if you don’t believe you have anything in common with other fat people.

Those who inhabit thin or ‘normal’ bodies may not ever consider the possibility that they may become fat. They may believe that they are thin due to personal superiority, or that they are simply putting more effort into their health than the fat people in their lives do. It’s hard to imagine that you might be fat one day regardless of your self-control, your actions, or your intentions.

Bodies are not as closely controllable as we like to imagine that they are, or as controllable as capitalism would like them to be for the sake of productivity. Human life and human bodies are unpredictable, changeable, and fragile. This may be a scary thought, and certainly brings mortality closer than we would like it to be. Fatness is a memento mori for society, and that society is trying to keep it in a draw, concealed at a safe distance.

We need to embrace and comprehend what fatness means more fully, and create a society where bodies are respected and free. Even if fatness were a choice, it should not be used to strip people of their dignity or their basic right to happiness and acceptance.

Fat spaces are so important in breaking down these barriers: they nurture the creation of fat friendships, and therefore the basis for solidarity. They offer freedom from the projected limitations placed upon fat individuals by society, and they are strong evidence that fat people are valuable and have something to offer.

The first step towards mutual aid and recognition of mutual struggles for equality lies in spaces such as these.

Cat Lawton-Westerland grew up in Cardiff and studied languages in Birmingham. She lived in Austria before moving to Glasgow in 2017 and completing a masters in linguistics. She is interested in body politics, disability studies and critical analysis.

Some further reading for those who are interested:

Podcast: Maintenance Phase: a podcast which explores and debunks health and wellness myths

Podcast: The Fat Lip: A fat liberation podcast [http://thefatlip.com/?fbclid=IwAR1ufX4XvoSR9diYWQmbtgHNDYftCZGBs1-IUkEc8UXymaHOS_bQdiCILwo]

Article: Fat Women: The Role of the Mother–Daughter Relationship Revisited

Article: Wombs at Risk, Wombs as Risk: Fat Women’s Experiences of Reproductive Care (any article in Fat Studies is probably worth reading)

Article: ‘Gluttony or Sloth’: Critical Geographies of Bodies and Morality in (Anti)Obesity Policy

Comments ()