No amount of sustained organising is going to remove the need to engage in conflict. Conflict not in order to change minds, but to protect ourselves against those whose minds are firmly made up.

By Panos Theodoropoulos

This intervention is kept short on purpose. While it could expand into significant detail, it is not intended to be a text of radical media for leisurely consumption; it is meant precisely as an intervention, in order to clarify a misconception and inform action.

The Trump inauguration is nothing more than the triumphant confirmation of a process that has long been unfolding. Many of us know this, and it is not necessary to recount it here. This process fundamentally involves violent class war, with its accompanying racial, carceral, ecocidal, genocidal, and patriarchal forms. And while the ruling classes have been orchestrating it consciously and consistently – albeit not always through the same strategies – for centuries, there are certain signs, like Trump in office again, that really bring home the extent of the rot. In this sense, witnessing current developments is reminiscent of climate change: you only really realise how bad it’s become once your house burns.

Confronted with the flames – or, perhaps, as the ashes settle – we try to assess why the disaster happened. Of course, these assessments are themselves informed by the wider theoretical and political goals of those expressing them. In the left (whether ‘liberal’, ‘progressive’, ‘radical’, etc.), most assessments of defeat – the disaster – can be split as belonging to two camps.

The power of capital

The first camp locates our current historical defeat – the Trumps, the genocides, the dreary sense of impotence – in the power of our opponents.

Thousands, millions of pages have been dedicated to analysing how neoliberalism and neocolonialism established themselves as the dominant forces of our contemporary world. We have all read the (erroneous) accounts of the destruction of the strength of the nation states in the face of globalisation – a position ridden with a perverse nostalgia for an inclusive welfare regime that never was. We have all lamented the decline of strong unions. We have all read about the widening income inequalities across the world, and shared statistics about X percentage of people owning Y percentage of capital. We have all expressed horror at the geopolitical assaults that massacre innocents with impunity. We have all witnessed systemic institutions such as the United Nations and international law being exposed as pathetically inadequate. And, most recently, we have all been amazed at how a depraved cyborg can openly throw internationally-televised Nazi salutes, simply because he's rich.

The extent to which the rich have abandoned any democratic façade and now blatantly flaunt their authority is insulting, and we live with the insults, attempting to understand what precise combinations of events allowed them to piss on us all with such aristocratic arrogance. Yes, the powerful have become more powerful.

Movement failure

The second strand of explanations is more productive. It understands that the rich are the rich, and the rich will always attempt to consolidate and extend their authority. It understands that the anemic ‘class consensus’ of the Fordist welfare state in the West after the Second World War depended upon very specific strategic compromises by the ruling class, and was never intended as a long-term arrangement. It understands that even this brief ‘consensus’ was underpinned by violent colonial excursions outside the West. It understands that capitalism, from its inception ‘dripping with blood and dirt’, as Marx famously wrote, would never be humane. Simply put, it understands class dynamics and class conflict.

Understanding what the enemy does is extremely important; but the rich are the rich, and they will do what it is in their interest to do. Saying that your house burnt because of a fire is not exactly a revelation; understanding what you could have done to prevent the fire is perhaps more useful moving forward. This is a recognition of the essence of class war: we are in it, and our survival depends on what we do. Therefore, this camp analyses our own shortcomings.

My own work is fully invested in this line of thinking. In a forthcoming book, I write about the inexistence of unions and social movements from the communities that most need them; in the absence of alternative, inspiring narratives and empowering institutions such as unions and community centres, the dominant logics of neoliberalism are allowed to fester. Workers look up to Bezos rather than looking up to each other. Racist ‘solutions’ to economic problems proliferate. The Sun dominates the canteens of factories and warehouses. Your uncle literally thinks that George Soros is leading a conspiracy to turn you gay. The bots that increasingly saturate social media do a good job of enforcing these ideas. You come to believe that it's fight or die. These processes explode through racist pogroms in the streets of the UK. They are expressed through Trump in the US. And the more social movements are absent from the daily lives of the most impoverished communities, the more we will keep losing.

However, this position – while I believe it to be correct – can carry a dangerous assumption. From the pen of the brilliant late organiser and theorist Jane McAlevey, we read that most well-meaning charities and Social Movement Organisations (SMOs) ‘are directed by professional, highly educated staff who rely on an elite, top-down theory of power that treats the masses as audiences of, rather than active participants in, their own liberation’. This directly leads to disempowerment, as avenues for empowerment are severed from their grassroots… well, roots. In turn, this enforces the neoliberal/racist/patriarchal processes that feed our defeat, as disempowered people turn to authoritarian leaders and familiar ethno-nationalist identities instead of each other.

So far, so good. Makes sense, and it is consistent with the anarchist, communist, and autonomist ideals that I – and so many others – want to believe that we are fighting for.

However, this position can suggest that if only we organised correctly, if only we did tick all the boxes that are necessary for sustained, deep, immersed organising, if only we found the magic combination, the workers, the marginalised, and the exploited would be convinced of their objective interests and unite against our common oppressors. And this is where I think that many commentators misunderstand what we are really faced with.

The seduction of fascism

There are many reasons to believe that a large portion of the population will be convinced through better organising. How to precisely orchestrate such a campaign remains the task of everyone who cares an iota about basic human solidarity.

However, there are also many reasons to believe that another large portion of the population simply does not care. Not only do they not care, but they are reveling in the decay. We live in a social system that is saturated with competition, in which social Darwinism subtly but forcefully permeates almost every social interaction. The proud sadism expressed by Israeli soldiers all over social media, with millions cheering them on, is just an acute expression of a wider tendency. Increasingly, this social Darwinism is openly dominating the mainstream, expressed through dangerous idiots like Andrew Tate and even more dangerous scholars like Jordan Peterson. Authority is not only repressive: it is also productive, erotic, sadistic, seductive, at the same time as it is repressive; the love for it is not simply a product of workers being ‘duped’, but can be a result of their conscious identification with it.

In his recent book Late Fascism, Alberto Toscano talks precisely about this seemingly contradictory coexistence. Moving through radical Black and feminist texts, he reminds us that fascism is not something that re-emerged after 2016, but a foundational aspect of capitalism that existed alongside and within the previously liberal institutions and societies. Citing Adorno, he then talks about the masses coming to desire social catastrophe, particularly ‘when your economic prospects are dim but you fear social transformation’. Through Guatarri and Deleuze, he points to the existence of seeds of fascism in us all, subtly permeating our everyday relationships, ready to be fully unleashed when the tides of history change. Crucially, he cites Foucault and his argument that fascism does not simply remove power from the masses; it correspondingly gives power to certain elements of the masses.

This is the power of the overseer, the prison guard, the SS: the power to control another human, violently puking your desire for authority over them, engulfing them and yourself in it. This limited and seductive form of power can be particularly enticing for disempowered populations, offering opportunities for enacting personalised fantasies of domination. And indeed, if reports are correct, an unprecedented number of minoritised workers voted for this iteration of the Trump administration.

I will not write more about Toscano’s book, but the argument here should be obvious. It is consistent with history, where groups of oppressed workers routinely sided with the oppressor, in exchange for crumbs of power. Whatever the reasons that many workers today identify with fascist or borderline fascist ideals and symbols – and, of course, the impotence of radical social movements is chiefly to blame – the fact remains that many do, very consciously, passionately identify with them.

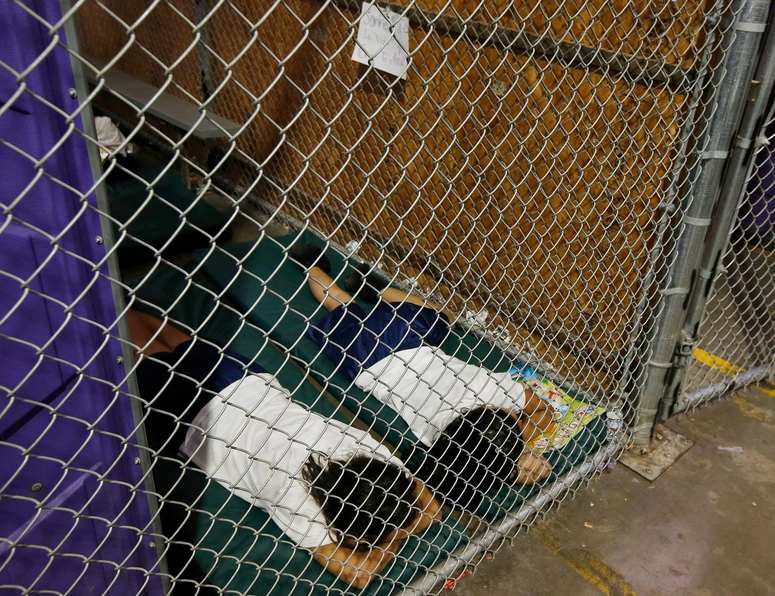

No amount of sustained organising is going to remove the need to engage in conflict. Conflict not in order to change minds, but to protect ourselves against those whose minds are firmly made up. Unfortunately, people have not been only duped. Those who voted for Hitler were not misled. The white US workers who became complicit in slavery eagerly exchanged class solidarity for the wages of whiteness. Those that voted for Trump again, with the memories of children in cages still fresh, knew who they were voting for. Perversely, many might actually enjoy the image of children in cages.

This is not a realisation that complements the belief in fundamental human instincts of solidarity and compassion nurtured by so many progressives/radicals/leftists/etc. in order to feel hopeful. While these reflexes do still exist – and the mutual aid efforts that spring up during and after every environmental disaster are indisputable affirmations of their endurance – it is also true that for a large part of the population, they have been replaced with raw, visceral hatred and a romanticisation of fascism.

This realisation is uncomfortable because it attacks our need to think that we can control our collective destiny. We need to believe that, if only we find the magic formula for organising resistance, we will inevitably bring people to our – their – struggles. However, we must realise that organising is impossible without confrontation. There was a time when better organising could have prevented the turn towards fascism. That time has passed. The soothing touch of community love and solidarity will not magically cure the brutality of someone who enjoys the idea of drowning migrants.

While deep organising is more important than ever, it is also important to seriously engage in building institutions of community defence. These go beyond organising combative antifascist networks: for example, I would argue that having lawyers on our side, or establishing strong unions precisely to fight racism where it is born – in our system of labour, expressed through our disempowerment as workers – are fundamental needs. Indeed, there are strong arguments that one side (community organising) will organically feed the other (community defence), both leading to stronger movements.

I do not want this article to be perceived as a blind invitation to attack those we deem to be fascists, or reproduce systemic narratives about racist working-class thugs. I do not want to detract from the importance of organising in communities – particularly those most vulnerable to the allure of fascism – or of directly engaging with people who we disagree with. I simply want to stress that only outreach and community engagement will not suffice.

We do need to understand our enemy (capital), and we do need to understand our shortcomings. But we must also understand that many members of our own communities will gladly aid the fascist project. We must be honest about the fact that our neighbours, our parents, and our colleagues may have chosen sides. Many will not join us, no matter how well we try to organise alongside them. It is only with this in mind that we will be able to defend each other. Without this defense, we might not have very much left to organise.

Panos Theodoropoulos is a sociologist and member of Interregnum. He is currently based in London and is organised with the Industrial Workers of the World.

Comments ()