Most think of copyright enforcement as a tool to protect the entertainment industry from pirated content. However, copyright enforcement systems have become a shadowy frontline in the suppression of dissent and the curbing of free expression.

By Sevra Guzel

When people think about copyright enforcement online, they often imagine takedowns of funny TikToks or YouTube mash-ups featuring copyright-protected songs. Most think of copyright enforcement as a tool to protect the entertainment industry from pirated content. However, copyright enforcement systems have become a shadowy frontline in the suppression of dissent and the curbing of free expression.

Online copyright enforcement uses automated content recognition technologies commonly referred to as ‘upload filters’ that scan data either when it is uploaded or before it is published on a platform. The main technology behind upload filters is fingerprinting. In simple terms, software turns a song, video, or image into a string of numbers called its ‘digital fingerprint’ and stores it in a database. Every time you upload something, the system scans it against this database. If there’s a match, your post can be blocked before it ever goes live.

The system is far from foolproof: its accuracy depends on the quality of the data it has been trained on and the thresholds set by the platform. That means that it often misidentifies or overlooks content, leading to takedowns of perfectly legal material. These filters are often integrated with copyright content management systems: platform tools that allow rightsholders to automatically block, remove, or monetise material at scale, concentrating even greater control in the hands of major players.

Unsurprisingly, malicious actors realised that these tools do not have to be mere technical appendages for intellectual property enforcement, so upload filters and content moderation systems increasingly have come to function as censorship engines. Their (mis)use is expanding beyond traditional rightsholders and is being co-opted by governments, law enforcement, and other powerful actors to avoid scrutiny and accountability.

Copyright systems are being deployed to silence critics, suppress dissent, and launder censorship through opaque technical systems. These tools now threaten not just digital creators, but anyone who uses the internet for the purposes of information, expression or dissent.

Fundamental Rights

The protection of freedom of expression is vital for holding power to account, enabling public discourse and safeguarding democracy. Through user-generated content, every day more people are using these platforms to partake in democratic society by commenting on matters of general interest, sporting issues, performing artists and political debates.

Enshrined in the European Convention on Human Rights (Article 10) and the EU Charter of Fundamental Rights (Article 11), freedom of expression includes not only the freedom to speak but also to receive and impart information without interference. The Council of Europe has accepted that freedom of expression includes the right to access the internet, underlining the importance of the internet regarding communication, users’ democratic participation and the expression of ideas and opinions. While this article is rooted in EU law, it is important to note that similar tensions exist elsewhere. The United States protects freedom of expression under the First Amendment, while other jurisdictions such as Turkey have constitutional guarantees of ‘freedom of expression and dissemination of thought’ (Article 26 of the Constitution of the Republic of Turkey).

In addition to freedom of expression, the right to a fair trial and an effective remedy (Article 6 ECHR, Article 47 EU Charter) is also under threat. These rights guarantee access to legal recourse, including being notified (with justification), being heard, and receiving independent adjudication. Yet today’s copyright enforcement systems often sidestep all of these safeguards. When content is blocked, removed, accounts suspended, or creators penalised, it usually happens without clear notification, explanation, or opportunity to appeal. This amounts to a system of shadow justice, where algorithmic processes replace courts and private actors act as judges. The combination of lack of transparency and accountability, as well as the inappropriate transfer of juridical authority to the private sector, creates a very dangerous environment for fundamental rights.

It is also important to consider that, as copyright operates territorially but platforms operate globally, the enforcement tools we are discussing have transnational effects. A filter deployed in the EU is not just applied to EU users but to everyone uploading worldwide. This global reach means that safeguards embedded in one jurisdiction’s framework may not meaningfully constrain misuse in another jurisdiction. The result is a fragmented but interconnected enforcement landscape where local abuses have global consequences. Understanding this global-territorial tension is essential to grasp why examples from the all different parts of the world illustrate the same underlying danger: the weaponization of copyright enforcement against fundamental rights.

Copyright as a Repressive Tool

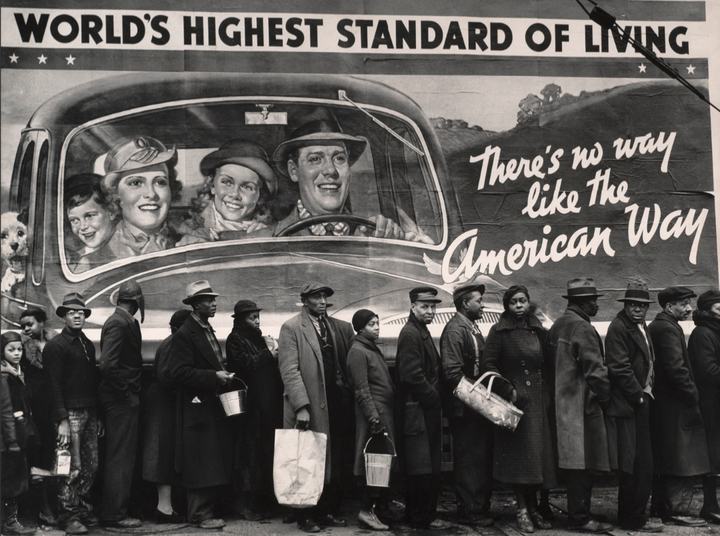

1: Police using music to avoid accountability

As always, the United States stand at the forefront of demonstrating how legal protections can serve the curtailment of freedom. One of the clearest examples of this abuse is by law enforcement officers who deliberately manipulate copyright filters to avoid public scrutiny. Videos have surfaced of U.S. police officers playing music from their phones while being filmed by activists, knowing that social media platforms will detect the music and block the video due to copyright claims.

In July 2021, a Beverly Hills officer was caught playing Taylor Swift songs while being recorded by a member of the Anti Police-Terror Project. This was during a protest outside the courthouse at the pre-trial hearing of a San Leandro officer charged with the manslaughter of a Black man. Unfortunately, the cop was not a die-hard Swiftie: in the video, he says, ‘You can record all you want, I just know it can't be posted to YouTube.’

In another instance, cops used Beatles tracks to trigger takedowns on Instagram. This time, they played the classic Yesterday. Even the choice of songs shows that the police are well aware that they are triggering Instagram’s algorithmic copyright filters so that videos of their interactions with the public will be taken down. It is important to note that repeated infringements can result in the suspension of the users’ accounts.

Even peaceful interviews with protesters have been removed due to background music triggering copyright blocks, such as when Marvin Gaye’s Let’s Get It On was picked up during a protest livestream. What was erased here was not piracy: it was historical footage of Black resistance, censored because a Black artist’s copyrighted work was playing in the background. The irony is brutal. Legally, this kind of incidental use during live reporting would fall squarely within copyright exceptions such as news reporting (s.30, CDPA 1988). In reality, no rightsholder’s legal team would dare bring this to court, as they know it would not stand. However, why bother when automated takedowns can enforce what the law does not?

These are not isolated cases. There is empirical data on how music in videos filmed at protests has repeatedly resulted in them being removed from social media sites on copyright grounds. At first glance, these takedowns can be framed as accidental collateral damage from overzealous automated filters rather than as deliberate censorship. However, that narrative is wearing thin. The pattern reveals a consistent, targeted effect: using the threat of copyright enforcement to disrupt and erase the documentation of state violence. Once this tactic is recognised, it becomes impossible to dismiss as mere algorithmic clumsiness. It is clearly a tool of control cloaked in the language of copyright protection.

2: Governments misusing copyright for political censorship

Governments quickly realised that copyright takedowns are convenient tools for political censorship. Why bother with slow, visible, and legally risky state censorship when you can quietly piggyback on private content moderation systems? Through upload filters, algorithmic enforcement and opaque ‘rights management’ tools, politically inconvenient material can be erased before it ever gains traction.

These systems thrive in the shadows. Users frequently receive no clear explanation (and, in some cases, none whatsoever) when their posts are filtered out or blocked by an algorithm. Decisions come from a black box: no human reasoning, no accountability, just the blunt force of automated compliance. AI-driven moderation is particularly dangerous here because its complexity and proprietary nature make it almost impossible to audit from the outside.

The secrecy is inscribed in law. How upload filters operate varies wildly from one platform to another, but most of that detail is locked away: platforms are not required to disclose certain types of information. The carve-outs that allow platforms not to disclose information which would compromise the integrity of automated systems or expose vulnerabilities can be grounded in Article 16 of the Charter. This article enshrines the freedom to conduct a business, and encompasses the protection of sensitive operational know-how, trade secrets, and the integrity of technical systems.

Even where platforms disclose aspects of their operations as mandated by the law, they find ways to provide cherry-picked information and very limited data about the operational underpinning of their technologies and overall content management. So, we, the public, end up with a handful of feel-good metrics, stripped of the context needed to understand the scale, scope, or political misuse of these technologies. Google, one of the most prolific operators of such systems, is particularly infamous for this selective openness. Their glossy transparency dashboards are just another algorithmic feed, this time serving reports instead of posts, so even outside their platforms we are fed their curated reality.

These technologies therefore represent perfect tools for a 21st-century censorship infrastructure, bypassing classical legal and political checks. Instead of crude bans or court-ordered injunctions, this suppression happens quietly, buried in the opaque workflows of algorithmic moderation and automated rights management.

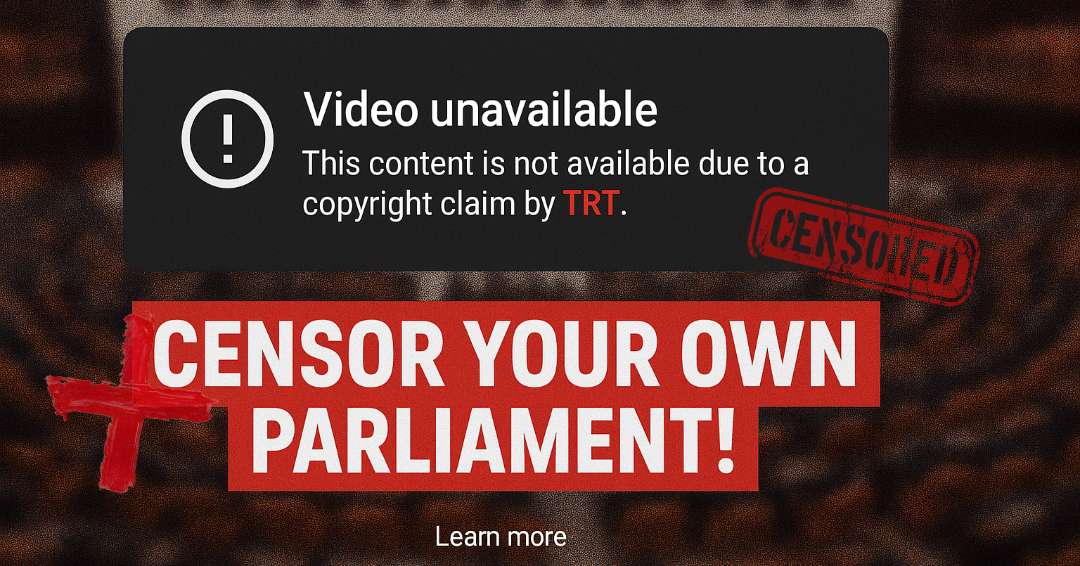

Turkey provides a prime example of how the above tactics can be used for political censorship. The Turkish Radio and Television Corporation (TRT), the national public broadcaster, has played a significant role in copyright-based censorship of critical YouTube channels. As a major rightsholder, TRT uses YouTube's copyright system to file takedown notices against videos that are critical of the Turkish government. One notable example is Bold Medya, a German-based YouTube channel run by exiled Turkish journalists. Bold Medya had exposed police violence, corruption, and state oppression, but was hit with copyright claims despite using no TRT content. Ultimately, the channel was shut down once YouTube’s three-strike threshold was surpassed, without a court or public scrutiny.

Taking these tactics a step further, TRT also targeted Meclis TV, the parliamentary channel that broadcasts general assembly sessions. Of course, this is footage that should be in the public domain or freely accessible. The broadcaster flagged videos containing sharp criticism of the government, effectively suppressing opposition deputies whose voices were already banished in traditional media.

More recently, a 2025 investigation by The Guardian revealed that Google complied with hundreds of takedown requests from authoritarian governments, particularly by China and Russia, which were filed under the guise of copyright claims. In reality, the targeted content often included investigations into corruption, political dissent and footage of protests and police brutality. These removals, hidden under the cloak of copyright enforcement, show how copyright takedown systems are being used for political repression.

Context-Blind Technology: Filters That Cannot ‘Understand’

On top of this intentional misuse of copyright management systems (access to which platforms grant only to big rightsholders), there is another challenge for online freedom of expression. Upload filters are often justified as necessary for enforcing copyright at scale; however, these systems are context-blind. They cannot identify all infringing content accurately because drawing the line between lawful and unlawful content usually requires contextual analysis. Filters are often unable to understand the nuances between unauthorised uses of copyright-protected content and uses that fall within the sphere of statutory copyright exceptions and limitations.

Many studies have noted that even advanced filters are incapable of recognising nuances such as satire, parody, protest, or regional dialects. They operate through crude matching techniques, detecting similarities in sound or visuals without any understanding of why the content is being used. From livestreams which include fully licenced content (Michelle Obama’s speech was blocked by Content ID because it included a brief clip from Doctor Who) to parody videos (automated copyright claims by Constantin Film forced YouTube to pull hundreds of Downfall ‘Hitler bunker’ parodies, a widely recognised form of online satire that was often used for political commentary), no form of expression is safe. This is quite concerning as copyright exceptions such as parody and quotation have traditionally constituted a cornerstone regarding the fair balancing of the rights of users against those of rightsholders, but the required enforcement tools are blind to them.

This blindness leads to over-blocking: not only is infringing content removed, but also legal content that benefits from copyright exceptions such as quotation, criticism, review, and use for the purpose of caricature, parody or pastiche. With Article 17 of the EU’s Copyright in the Digital Single Market Directive (CDSMD), the protection of these exceptions are now mandatory for all for EU Member States. Yet the filters do not know that these types of uses are protected by law, nor do they know when copyright protected content is merely incidental, which is also another statutory copyright exception (e.g., music playing in a protest video). The result? Legally protected expression is removed from the internet before it ever reaches an audience.

Right now, the legality checks on anything you upload are left to rightsholders (who are hardly neutral) and to context-blind upload filters. These filters’ ‘efficiency’ depends on the accuracy (and honesty) of the data fed to them by rightsholders. This creates the perfect recipe for wiping out not just freedom of expression, but also any hope of a fair process. As the big platforms are where so many people actually speak, create, and share, the damage is concentrated right where it matters most.

User-generated content takes the biggest hit. A large body of research shows that, under the current operation of upload filters, without meaningful or efficient ex-ante and ex-post safeguards, there is no guarantee that restrictions on freedom of expression are proportionate. Filters are error-prone by design, and false positives are built in. Lawful posts, including ones that should be protected by copyright exceptions, get blocked without a human ever looking at them.

Why? A whole list of reasons: filters designed without nuance, bad data in the fingerprint databases, a total lack of transparency, and systems that are ripe for abuse. Add in the fact they have no idea about context, and you get what we currently have: machines pre-emptively killing expression just in case a rightsholder might complain.

Bug or Design?

It is easy to frame wrongful takedowns as harmless glitches, as unfortunate but inevitable errors in otherwise neutral systems, but the evidence shows a consistent pattern: these so-called mistakes almost always work in favour of those with power and against those without it.

When copyright enforcement allows police to suppress video evidence, governments to block dissent, and corporations to remove criticism, it cannot be seen as accidental. It is part of the design: platforms prioritise compliance with powerful actors over the rights of individual users, and filters make that compliance invisible.

As platforms rarely disclose the criteria for takedowns or the filtering rules that prevent content from ever being uploaded, users are kept in the dark about what is actually permissible. Preventive filtering ensures that many forms of expression never even reach the public, making censorship often invisible and unchallengeable. Combined with appeals systems that are slow, opaque, and often futile, this leaves users with no meaningful way to contest decisions. There is no effective remedy, no transparency, and no accountability, which means there is no justice for user's rights. This is not the rule of law. It is rule-by-algorithm, administered by private intermediaries on behalf of whoever has the most leverage.

However, this rule-by-algorithm architecture is no accident: Article 17 of CDSMD, the same article that made some copyright exceptions mandatory, explicitly requires platforms to prevent the availability of copyright-infringing content, effectively mandating automated filtering. This was not a neutral or technocratic outcome. The Directive was the product of an intense lobbying campaign by rightsholders. Public records show that from late 2014 onward, over 93% of all lobby meetings on copyright were held by corporate interests, especially the International Federation of the Phonographic Industry (37 meetings), the Federation of European Publishers (27), and The European Grouping of Societies of Authors and Composers (25), dwarfing engagement from NGOs or user advocates. The voices of civil society, organisations working on human rights, academics, libraries, UN Special Rapporteur Kaye, and even Tim Berners Lee (Sir World Wide Web) were comparatively muted, despite mobilising widespread public support: remember the #SaveYourInternet campaign, internet blackouts, and millions signing petitions.

The net result is a law that, while framed as balancing the rights of freedom of expression with copyright protections, established this form of imbalanced automated enforcement, integrated into the legal framework by the very actors who stand to benefit most from its enforcement mechanisms.

Conclusion: Community as a Shield!

Automated copyright enforcement has outgrown its original purpose. Instead of protecting creative labour, it now increasingly functions as a tool of control. From law enforcement officers exploiting upload filters to governments disguising censorship as copyright enforcement, the evidence is overwhelming. The systems are opaque, the impacts are severe, and the legal protections of users are collapsing under the weight of algorithmic governance.

Although I have dedicated at least five years of my ‘academic career’ to thinking about these issues, I do not have all the answers. As starters, I think it would be nice if government misuse of copyright tools could be dragged into the light. State takedown demands should be public, logged, and subject to independent oversight. Since mandatory upload filters such as those baked into Article 17 are a gift to lobbyists and a threat to free expression, EU Member States should use every inch of their implementation leeway to blunt their impact. Other jurisdictions should do their utmost to truly protect freedom of expression.

Procedural safeguards must stop being an afterthought: users deserve immediate notification of removals, a clear explanation, and a fast, accessible appeals process. For upload filters, there must also be ex-ante protection for freedom of expression; content should not be blocked before it is seen unless it is manifestly unlawful, with human oversight built into the process. In many other jurisdictions, similar safeguards can be achieved by activating and enforcing the protections already embedded in fundamental rights frameworks.

Above all, we need to build fairer platforms, shifting power away from corporate gatekeepers and toward decentralised, community-driven systems that cannot be easily weaponised against dissent; these systems should also prevent the irreparable harm done to freedom of expression by upload filters. That is why I argue for a Community Review Model inspired by Counter-Strike: Global Offensive’s Overwatch anti-cheat system: instead of filters killing a video the second an algorithm flags it, the content would be held for quick review by trained community members. Think of it like a jury of peers for freedom of expression online — adding human judgment, context, and fairness where machines only see ‘infringement’. Copyright as a weapon, community as a shield!

Until then, these tools will remain the quiet machinery of censorship: shutting down resistance, one algorithmic match at a time.

Sevra Guzel is a Senior Lecturer in Law at BSU and part of the arts collective Through the Cracks. Her work explores the tensions between innovation, regulation and fundamental rights.

Comments ()